Mangareva contains more diverse coral habitats than anything we have seen to date. Parts of the outside rim of the atoll are emergent. The cross sectional profile starts with a classic reef flat, 10 m wide in places and often extending more than 100 m from shore with small spillways connecting the lagoon and fore reef. At the seaward edge of the reef flat is a reef crest, where reef growth is vigorous. An extensive build-up of steep spurs. These project into the prevailing waves and are separated by narrow, deep channels. At the seaward edge, the slope plunges steeply to depths of 50 m or more. More than half of Mangareva is surrounded by a submerged barrier reef, 4-5 m deep at its shallowest point, with high wave energy and strong currents. The submerged barrier also has a characteristic “spur and groove” formation. The spurs here are much longer and wider and slope more gradually, stretching for 100s of meters between the lagoon and the deep reef.

Inside the lagoon are lagoonal fringing reefs, patch reefs, coral pinnacles, reticulate reefs, and an extensive deep water coral-encrusted lagoonal floor. Unlike other lagoonal habitats we have explored, vigorous coral growth occurs at the water’s surface, and many of the corals are periodically exposed at low tide.

Coral growth extends down the pinnacles, spurs or mounds to the lagoonal floor (25-30 m deep), and a deep coral framework on the lagoon floor supports a proliferant coral community to depths of 40 m or more.

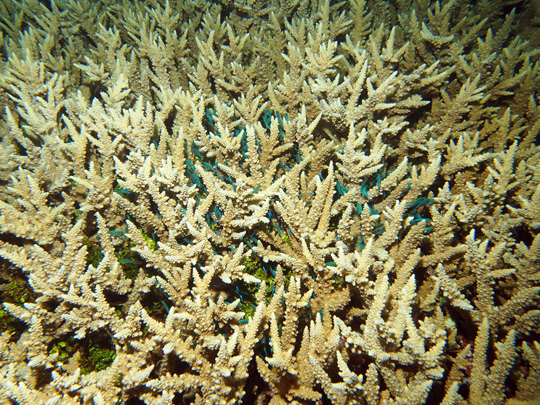

The shallowest part of the lagoonal reef has the highest diversity of corals, especially the genus known as Acropora. These acroporids take on a myriad of shapes and sizes: colonies have antler-like branches, low stumpy fingers, large flattened tables, thin, spindly branches, crusts, finely branched bushes, feathery spirals, bottlebrushes and more. They also can be yellow, brown, fluorescent blue, lime green, greyish white, red, or other colors of the rainbow. They are unique among corals in that they possess two very different types of animals or polyps – most posses a single a very large tubular “axial” polyp on each branch and hundreds of smaller radial polyps. These produce a very unique skeletal structure (known as corallite), which is used to help identify the species. The corallite is basically a tube divided into six or twelve partitions (called septa). Some of these corallites are tubular with round opening, some are pocket shaped, some resemble an earlobe and others look like an upside down nose.

We found dozens of species of acroporids on shallow lagoonal reefs, but these tend to occur in small clumps. As you go deeper, the clumps get larger, often forming vast single species thickets tens to hundreds of meters in length. This group and other corals also showed a very characteristic distribution or zonation pattern. One table forming coral that was rare or absent in all other locations we have examined thus far in French Polynesia, formed vast stands at intermediate depths (5-10 m). Below this, tall, thinly branched staghorn-type acroporids dominated.

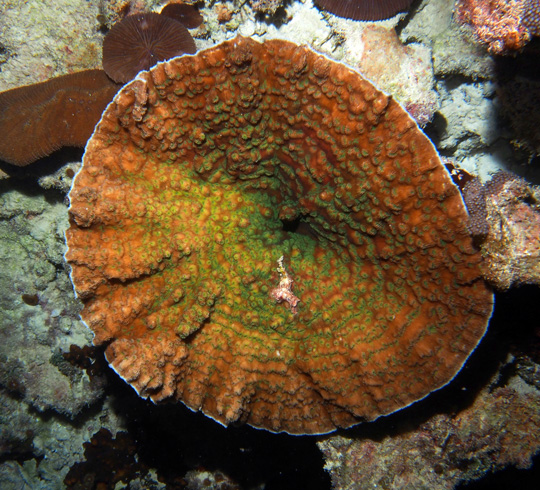

Still deeper, the acroporids become less common and piles of free living mushroom corals (Fungia, Herpolitha, Sandolitha) coexist- hundreds may accumulate in a very small area, most the size and shape of a large dinner plate.

Still deeper, corals form delicate plates, rarer species like the elephant nose coral (Mycedium), lettuce corals (Pavona and Leptoceris), and foliaceous Montipora. Often the base of the reef had massive colonies of Pore coral – individual colonies were 3-4 m in diameter or larger.

Perhaps most interesting, each lagoonal reef had a different structure and a different assemblage of corals. One of the biggest challenges we face is understanding why.

(Photos by: Dr. Andrew Bruckner)