The reef at Alice Shoal was an impressive site today, as much for the human activity as the marine life. Rising up a few meters off the bottom I spotted divers working in pairs around me as far out as I could see. In between them were the welcome sight of countless fish — angels, huge surgeonfish, and loads of exquisite black durgeons.

The reef here is in the 15 to 20 meter depth range, with most of the seafloor covered in algae and sponges. The contours are mild, with only the occasional rock ledge for fish or lobsters to hide beneath. There are corals here, but they’re sparse.

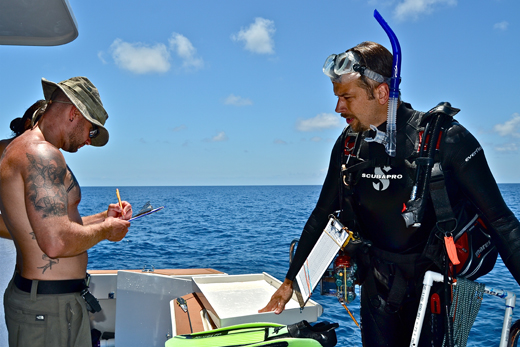

Each night the team comes together to discuss the day’s work. Tonight, the main topic was how much more plentiful, and in many cases larger, the fish are here compared to Pedro Bank, the site of an earlier mission. That’s not surprising, because Pedro Bank, about 130 kilometers northeast of Alice Shoal and much closer to Jamaica’s main island, is far less isolated, opening it to much heavier fishing. Here, we still haven’t seen a fishing boat.

On one dive this morning, I tagged along with Living Oceans Foundation fellow Sonja Bejarano. She’s setting up GoPro video cameras at various spots around the reefs where the team dives. Each camera records about 5 hours of video. That’s up to 50 hours of video per day, which she and whatever volunteers she can con, or enlist to help, will review once she returns to her home lab at the University of Queensland.

Sonja’s goal is to figure out which plant-eating fish, or herbivores, are coming to each site, and how much algae they eat. These fish are critical to reef health because they can keep algae growth in check.

Having just taken a quick look at the video, Sonja is finding that the herbivores here are plentiful. But so is the algae, and it’s not completely clear why that is.

Sometimes potentially pernicious algal species will smother sections of previously healthy coral. This can happen when coral are sickened or killed by warming waters or disease, when overfishing removes too many herbivores, or when there’s too much algae-fueling pollution and herbivores can’t keep up. With those kinds of shakeups, you typically see the skeletal remains of dead corals. We haven’t found that here. So, the thinking is that for whatever reasons, perhaps going eons back into geological history, the hard corals that build large reefs just never dominated this place, and so it enjoys its own algae-dominated balance. One of the benefits of the global reach of this multi-year expedition is that scientists will be able to make more sense out of the factors that shape reefs.

We’ll be working here at Alice Shoal for two more days, then heading east about 70 kilometers to a bank called Bajo Nuevo. There are a few islets there, but the area is mostly exposed, meaning little protection for the ship against rising seas. We hope to get a few days of work in before seas kick up as predicted. Then we’ll head west for the Serranilla Bank, which has a bit more land for the ship to hide behind. That’s the plan, but plans have a way of changing when you’re at the mercy of a fickle ocean.

(Photos/Images by: 1 Alfredo Abril-Howard, 2-4 Mark Schrope)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.