Expedition Log: BIOT – Day 2

For our first mission to the British Indian Ocean Territories (BIOT), our research is concentrated on the southern banks of the Chagos Archipelago. This area includes a number of small islands and atolls. Our first stop was Cauvin Bank, located about 7 km south of Great Chagos Bank. The bank is a drowned reef platform surrounded by a ring of coral that never breaks the surface. According to the navigation charts, there is an extensive area that is about 10 m deep off the northwest corner of Cauvin Bank.

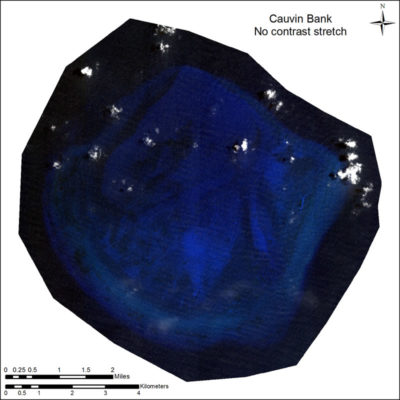

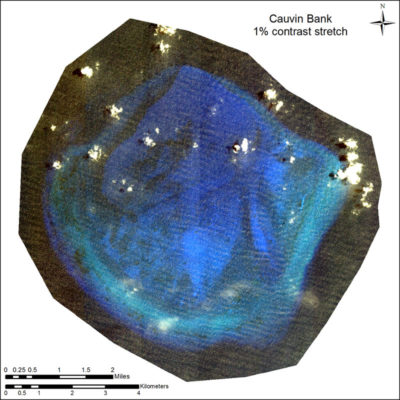

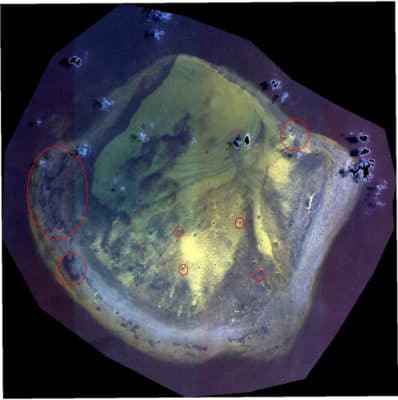

A satellite image of Cauvin Bank. The red circles depict locations that we thought were shallow and supported coral communities.

A scan of our high resolution satellite imagery suggested that this area contained reef habitat. The perimeter of the bank also appeared to have patches of coral and large coral bommies, reminiscent of what we’ve seen on other Pacific atolls were scattered throughout the lagoon (see red circles above). There also appeared to be extensive sandy habitats, most of which I assumed were only about 10 m deep. We selected a series of coordinates for potential dive sites, based on the imagery, and headed out for our first dive.

Arriving at the first point, which we thought was about 10 m depth, our chart plotter showed 35 m – too deep for our surveys. We slowly navigated around the bank searching for shallow water. After about an hour, we identified one location along the rim that was 18 m depth and went under to begin our surveys. From the surface we could see large dark areas, we predicted to be densely colonized coral patches. Surrounding these was a mix of sand and other dark areas also presumed to be reef.

A large meadow of turtle grass Thalassodendron ciliatum.

What we found couldn’t have been more different. A scoured hard bottom scattered with small coral colonies and coral cover of less than 1%. The seafloor was carpeted in sponges, colonial anemones and soft corals and erect green coralline algae (Halimeda) scattered over the bottom. Interspersed among this community were very dense patches seagrass. Even though the bottom was completely flat, it was teaming with life. There were hundreds of tiny coral colonies, most the size of a golf ball or smaller. What was most unusual was their growth form. These were species that typically attached to the bottom and grew into large colonies. But on this reef, most were free living “rolling stones” with live tissue completely encircling the colony.

One of the few larger corals, a colony of Gardineroseris planulata.

Small groupers, such as the blacktip grouper (Epinephelus fasciatus) were very common. (left) / A spotted trunkfish (Ostracion meleagris). (right)

(click thru on images for greater detail)

To better understand why I had misinterpreted the imagery, I had a discussion with our habitat mapping expert Jeremy Kerr. My understanding was that the satellite imagery we used was suitable to detect features on the bottom to about 25 m depth. But there were tricks of the trade that would bring deeper features into view. Namely ‘contrast stretching.’

Contrast stretching is one of the most common tools in remote sensing. Anyone who has turned off the lights in a room and then allowed their eyes to adjust to the dark has experienced how the human brain naturally performs a contrast stretch. The method artificially increases the difference between similar shades of a color thereby enhancing the distinction between them. The technique is very common, and many programs for displaying satellite imagery automatically perform a small linear stretch. In most cases, the difference between the stretched and natural, non-stretched image is minimal. In very rare cases, a small stretch creates a substantially different image. In the normal, unstretched image, Cauvin Bank is a deep shade of dark blue and the only bright areas are the clouds. With a small stretch, the bank’s seafloor features are distinguishable, and the whole area seems fairly shallow. The deep nature of the bank combined with the application of a very common method for image display tricks the brain into misinterpreting the bank’s depth.

Photos by Andrew Bruckner (except satellite images).