Expedition Log: BIOT – Day 5

Today we hear from Konrad Hughen, Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, about the process of coral coring and how it is being used to measure changes in climate in this remote region over the past several centuries. The information gathered will allow us to compare patterns here at Chagos with other regions around the world, and eventually help us to understand how the global climate system works on long timescales, beyond the limits of short instrumental and satellite records.

Today we hear from Konrad Hughen, Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, about the process of coral coring and how it is being used to measure changes in climate in this remote region over the past several centuries. The information gathered will allow us to compare patterns here at Chagos with other regions around the world, and eventually help us to understand how the global climate system works on long timescales, beyond the limits of short instrumental and satellite records.

Massive corals growing in coral reefs around the world are like natural hydrographic stations, recording environmental information day and night throughout their lives. Corals are actually colonies of tiny polyps like sea anemones, that secrete calcium carbonate skeletons and actually live only in a thin layer at the surface of the coral structure. The skeleton itself contains annual density bands, like tree rings, that allow us to determine the coral’s age very precisely. Colonies of the boulder coral Porites lobata can, in extreme cases, grow to be more than 10 meters tall and live up to 800 years. Typically however, large colonies reach about 4 meters tall and approximately 400 years in age. The coral’s calcium carbonate skeleton is built from components found in seawater, and therefore contains a history of the seawater composition and environmental conditions in which the coral grew.

Coral Coring at Danger Island: WHOI Associate Scientist Colleen Hansell assists me in taking a drill core from a Porites lobata coral growing off Danger Island. We have just added an extension rod and are drilling down for the second core segment. (left) Colleen and I then work to pull a core segment out of the extractor after lifting it from the hole. Note the core segments that have already been drilled and extracted, lying on top of the colony. (right)

(Photos: Justin Ossolinski, WHOI).

(click-thru on images for greater detail)

As paleoclimatologists, we use these coral skeletons to construct records of past environmental change, revealing shifts in sea surface temperature, salinity, nearby river runoff and even pollution. To do this, we use a special underwater drill to take core samples right down the center of the colony from top to bottom. Our system has a motor onboard the boat that pumps seawater at very high pressure down to the drill head, which turns the drill bit, a hollow tube with diamond grinding teeth on the end. The seawater is finally pushed down the inside of the drill bit to flush the powder cuttings out of the hole. The drill assembly is operated by hand using SCUBA and can take a continuous core up to 80 cm long. Each core segment is broken free and retrieved from the hole using a special extractor, and then an extension rod is placed above the drill bit and a new 80 cm piece is drilled. The process is repeated, with multiple pieces being brought out, until we break through the bottom of the colony into the sand below. The core segments fit together perfectly like puzzle pieces, and together make up a continuous record representing the coral colony’s entire life history.

I put the coral core together piece by piece on the seafloor, to check for length and completeness. This core measured more than 1.2 meters long with relatively short growth bands (<1 cm/yr), and may provide a record extending back as much as 150 years. (Photo: Colleen Hansell, WHOI).

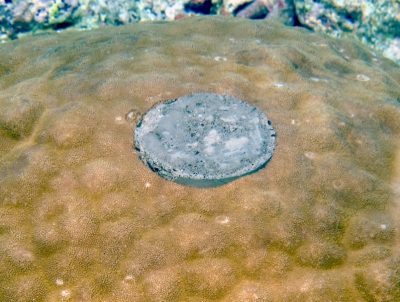

When coring is completed, we cap the hole using a concrete plug. The polyps surrounding the core hole will grow up and over the plug, completely covering and healing the scar within 1-2 years. Afterward, no one without a giant underwater xray would ever know a core was taken from inside the colony. We’ll take these cores back to our laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, where we will analyze the chemistry of the calcium carbonate skeleton. Trace elements within the cores are sensitive to environmental conditions like sea surface temperature, and we will measure elemental composition at 0.5 mm increments. For our longest core from here in Chagos, 1.8 meters long, this represents 3600 samples! These samples will reveal changes in temperature at about bi-weekly resolution, or one measurement encompassing every two weeks. These detailed records will show how the climate in this remote region has changed over the past several centuries, and allow us to compare patterns with other regions around the world, and eventually help understand how the global climate system works on long timescales, beyond the limits of short instrumental and satellite records.

We’ve placed a concrete plug in the drill hole to prevent bioeroding organisms from taking up residence inside the colony. Porites corals grow so fast that the scar will be gone after only a couple of years. (Photo: Konrad Hughen, WHOI).