Corals in tropical reefs are like trees in a forest. We all know from the tiny acorn, the mighty oak tree grows but where do the mighty corals come from? You’d think we know all there is to know about where baby corals come from and how they get started on coral reefs but we don’t. When I started graduate school no one knew how or when coral reproduction occurred.

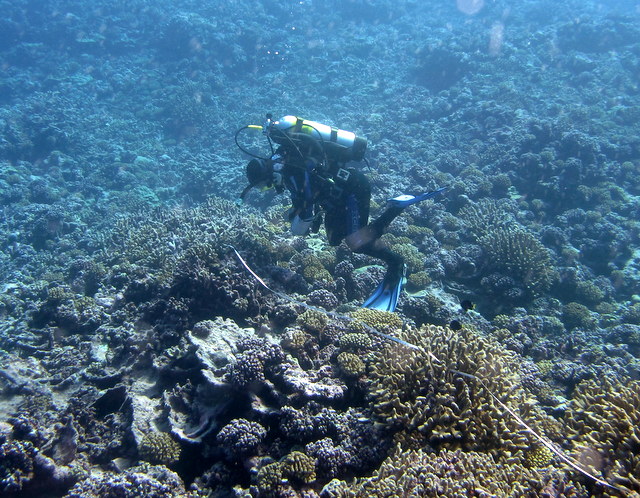

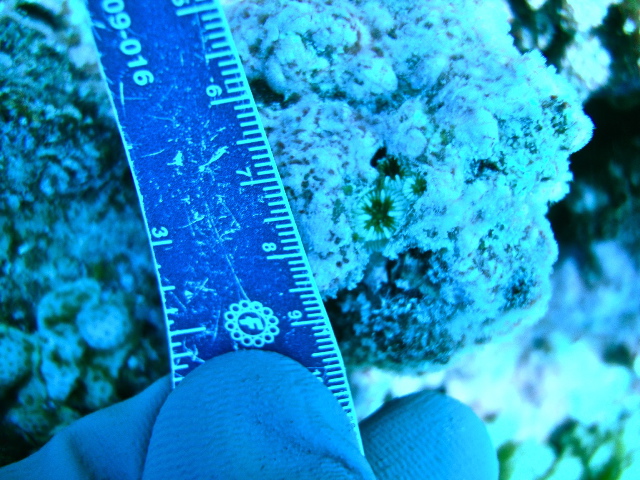

Then coral spawning was observed – it is linked to the full moon in late summer and when it happens it is like a snow storm in reverse. Tiny white bundles of coral eggs release all at once and float to the surface. They get fertilized and a small oblong larva covered in tiny hairs (cilia) floats until it develops into a baby coral. The trick for this tiny larva (which is about the size of a pencil dot on a piece of paper) is how does it find a good place to live in a coral reef. Coral larvae are blind and they cannot swim, but they can adjust their buoyancy. My research considers the environment baby corals encounter that affect their choice of where they will glue themselves to the reef and begin their long life. Most coral reefs are comprised of coral (logically), but corals are terrible places for larvae to settle since they’d get eaten. So the rest of the coral reef that is mostly covered in different types of seaweeds can be tasted and evaluated by the tiny coral larvae. The bigger seaweeds are bad places for baby corals – the seaweed can beat them up and some seaweeds can poison the newly settled corals. However, limestone producing coralline algae is a different story.

Some of the coralline species actually attract baby corals, allowing them to settle where they grow best and fewer of them die. My research examines that association. I consider how receptive different coral reefs are to settling coral larvae. Reefs that have more “recruitment” of baby corals, will recover quicker from a hurricane, crown-of-thorns starfish outbreak or a coral bleaching event. Figuring out how baby corals get started on reefs may help managers and policy makers improve the fate of these stressed ecosystems.

(Photos by 1 & 2 – Brian Beck; 3-Bob Steneck)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook!