The Golden Shadow arrived at Puerto Villamil, on the southern end of Isabela Island, last night. It is the third-largest settlement, and the largest island, in the archipelago. Today we explored shallow lagoons near the town’s docks, in particular one called Concha y Perla (Conch and Pearl), popular with tourists for its fish, curious sea lions and—good guess—its’ corals.

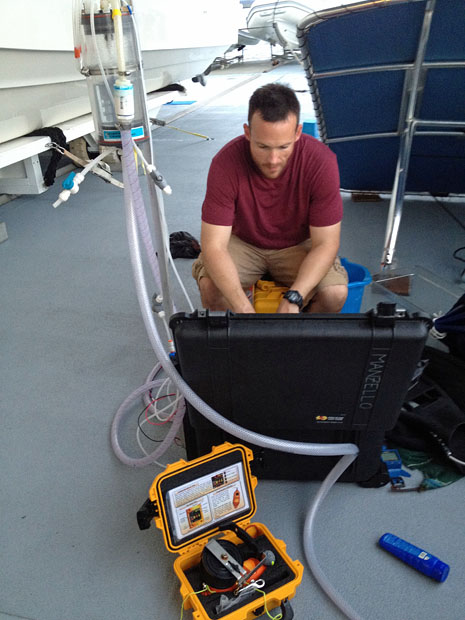

Today, like most days, Derek Manzello of NOAA hauled a pneumatic drill and an extra tank to power it on his dive, and he brings back bottles full of seawater back to the Golden Shadow. The drill is for taking cores to measure how fast corals are growing, like a tree core tells a tree’s growth rate. The seawater is for measuring carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. This greenhouse gas that we all exhale can also affect the health of coral reefs, and Derek is looking at how the Galapagos can help us predict the fate of corals around the world.

The deep-water upwelling that brings so much life to the waters in the Galapagos also brings an abnormal amount of CO2. (As organic matter breaks down and sinks, one of the byproducts is carbon dioxide.) Part of the process of global warming is ocean acidification. Not all of the CO2 we’ve produced in the past century or so has gone into the atmosphere. About a quarter of all carbon dioxide produced has ended up in the ocean, where it makes the waters more acidic. This can weaken reefs by interrupting the creation of calcium carbonate, the chemical compound deposited by coral polyps that forms the hard structure of a reef. Reef framework samples Derek has taken in the Galapagos on earlier research trips have little or no secondary calcium carbonate cement, which may be one reason reefs in the islands are so ephemeral; at best, seawater high in carbon dioxide is just not the ideal environment for building enduring reefs.

Derek is testing the idea that maybe the Galapagos’ high-CO2 seawater, and the reefs that form there (or don’t) can serve as a window to the future for what’s going to happen to all tropical reefs as carbon dioxide levels keep rising. More specifically, the more extensive corals around the northern islands Wolf and Darwin might be a result of their lower CO2 levels compared to the waters around the southern islands. Is there some carbon dioxide limit beyond which coral reefs can’t recover from warming events like El Niño? In a larger sense, are regular El Niño events the reason reefs in the eastern Pacific are less developed than reefs in the western Pacific?

According to Derek’s research on this mission, the CO2 levels in the northern islands are about 40% higher than they were in preindustrial times, before we started pumping it into the atmosphere. (The atmosphere and the surface of the ocean are usually in equilibrium.) That’s the same as it is throughout the tropics—the signature of global warming. In the south, near Floreana, carbon dioxide levels are much higher, about twice what they were in preindustrial times. That’s a lot of CO2 coming from the deep. What kind of effect that has on coral resilience and persistence remains to be seen.

(Photos/Images by Julian Smith)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.