This guest blog comes from a former KSLOF fellow, Dr. Anderson Mayfield, who joined the foundation on many of our Global Reef Expedition research missions in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. A former student of the renowned coral biologist Dr. Ruth Gates, Dr. Mayfield studies coral health and physiology at NOAA’s AOML Coral Program and at the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. He continues to publish scientific papers based on data collected on the Global Reef Expedition, including his latest paper, recently published in the journal Oceans.

A new study finds that ‘pristine’ coral reefs may be a thing of the past, and the most resilient corals may be found in some unexpected places

As a naïve post-doctoral researcher back in 2012, I had an idea that was surely far from novel at the time: corals of far-flung, uninhabited atolls are in better shape than those closer to major human population centers. The logic was that these corals would be under global-scale stressors only (namely those associated with climate change), and not the threats that instead plague reefs close to cities (such as pollution and overfishing).

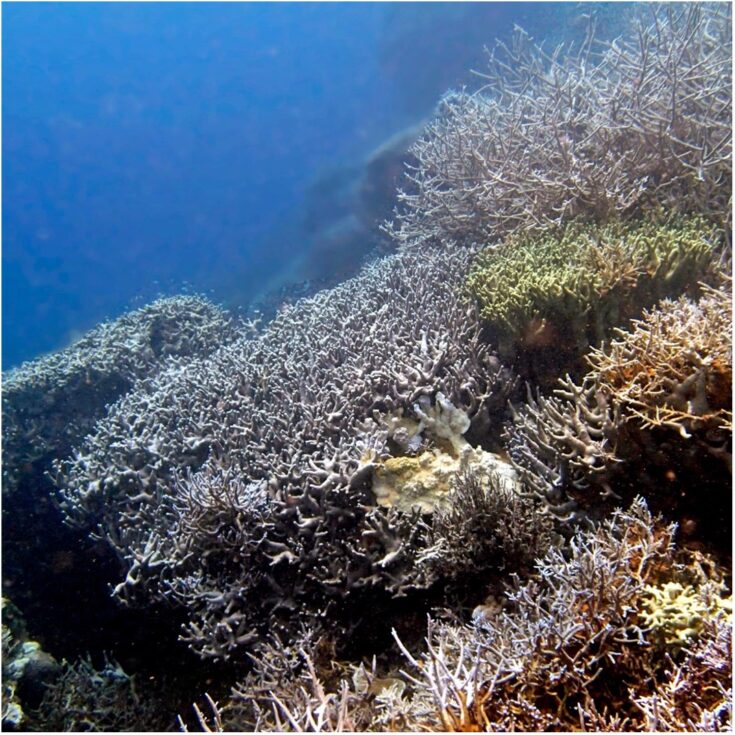

As a fellow with the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation during their Global Reef Expedition (GRE), I tested this hypothesis by sampling corals from among the most seemingly pristine islands and atolls in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Although we certainly observed beautiful reefs with high coral cover (see image above) and diversity as well as a plethora of fish —all the visible hallmarks marine biologists look for in ‘healthy’ reefs—the corals themselves told a different story (Mayfield et al., 2017); high cellular stress levels were documented in the vast majority of the many hundreds of corals sampled across the GRE.

Despite looking healthy, the corals were struggling to survive.

These high stress levels do not, in and of themselves, imply that all such sampled corals are not long for this Earth. They do signify, however, that we likely never visited ‘pristine’ reefs during the GRE, despite studying some of the most remote coral reefs on the planet. This is a testament to the wide reach of climate change. This statement may come as a surprise to some, who, like me, assumed that somewhere out there, one might find corals entirely untouched by humankind, but this unfortunately does not appear to be the case.

I assumed that somewhere out there, one might find corals entirely untouched by humankind, but this unfortunately does not appear to be the case.

Dr. Anderson Mayfield

Are there still incredibly beautiful coral reefs left on the planet? Certainly. Are there still corals, and even entire reef systems, that will persist into the coming millennia? I sincerely hope so. But it is important to be measured in our optimism by acknowledging this new normal with respect to coral reef biology. Researchers seeking even now to uncover ‘pristine’ coral reefs are setting themselves up for disappointment (at best) and could even be guilty of ‘environmental sugar-coating’ (at worst).

Instead, I suggest we see that a reef can still be resilient in the face of climate change, even if it is no longer ‘pristine.’

That said, there are unquestionably relative shades of ‘pristineness,’ and we looked at regional trends in human impact within the nations whose coral reefs we surveyed during the GRE. New Caledonia provided one such opportunity, with reefs of the south having been heavily impacted by mining operations (see images below).

Although coral reefs of the country’s far north are both far removed from human settlements and governmentally protected (only scientists are permitted to even visit them), we nevertheless documented stress marker levels in the sampled corals that were as high as those of corals of the same species found near megalopolises (such as the coastal cities of Taiwan). These measures were also far above ‘baseline’ levels characteristic of unstressed organisms (Mayfield & Dempsey, 2022). In other words, despite once again appearing ‘pristine’ on the surface (see image below), the corals’ physiologies had already been fundamentally altered by climate change impacts at the time of our surveys in late 2013.

Yet I still wonder, are the relatively more pristine corals of the far northwest of New Caledonia, despite exhibiting such stressed molecular signatures, more resilient than similar but more impacted corals of kilometers to the southeast?

Only time will tell, but, as it turns out based on findings from elsewhere in the world, it now seems likely that corals that have already been considerably marginalized due to deteriorating seawater quality are actually more likely to persist through the Anthropocene.

In a strange irony then, despite having directly or indirectly destroyed upwards of 70% of the world’s reefs over the past few decades, among the most resilient corals left on Earth are often those that have become inadvertently stress-hardened by having been forced to acclimatize or adapt to the ever-worsening conditions in which they reside (Mayfield et al., 2019). The lone survivors on a reef with few corals could very well be ‘healthier’ and more resilient than the myriad corals on a reef with no prior history of stress exposure (see image above). Reefs covered in corals will be more photogenic and consequently have superior tourist appeal, but not necessarily higher climate resilience.

Reefs can still be resilient, even if they are no longer ‘pristine.’

Anderson Mayfield

Nearly ten years on and with the power of hindsight, my original hypothesis now seems decidedly sophomoric; why would one expect coral resilience to be higher in places where the corals have known nothing other than balmy, clear, virtually nutrient-free waters?

In the years since our time in New Caledonia, many of the country’s reefs, as well as those elsewhere in the Coral Triangle, have bleached annually in response to rapidly rising temperatures, and through continued collaboration with on-the-ground scientists in the country, we can now test whether corals of the turbid, polluted waters of the most anthropogenically impacted region surveyed, Prony Bay (see image gallery above), are actually faring better than their relatives farther north, which have no prior history of significant, local-scale anthropogenic stress that may have pre-conditioned them to climate change-associated disturbance (see image above).

Even if this is proven to be so, it is surely not to say that we should seek to deliberately compromise seawater quality because of some accidental ‘success stories’ in creating mutant or stress-hardened corals (Rubin et al., 2021). It does speak to the fact that we be more open-minded in terms of where we go searching for coral reef refugia. As much as I enjoying SCUBA diving in the clear waters engulfing beautiful, colorful, diverse reefs with plentiful hard corals and other marine life, these may not be the best places to look for the resilient corals that will continue to contribute to reef formation into the distant future.

In the end, some corals will acclimatize, some will adapt, some will move, and some will perish, though where, and under which environmental conditions, we are likely to find high proportions of corals of each of these respective fates is clearly a topic we have yet to fully grasp.

Learn more

Learn more about corals in the Anthropocene in the latest scientific publication by Anderson Mayfield and our Director of Science Management, Alexandra Dempsey. The study, Environmentally-Driven Variation in the Physiology of a New Caledonian Reef Coral looks at the physiology of ‘pristine’ corals in New Caledonia just before the onset of severe annual bleaching events, so that future generations might know how these corals functioned in their last bleaching-free year.

Photo of Dr. Anderson Mayfield sampling corals on the GRE: ©Keith Ellenbogen/iLCP.