Expedition Log: Cook Islands – Day 12

As we bandage our wounds, wash and pack our gear, and prepare for our departure, we take time to discuss the outcomes of our project with our partners in Aitutaki. Since discovering and reporting the outbreak in 2013, the Aitutaki community has become much more aware and educated about these voracious predators and the impact they’ve had on Aitutaki’s reefs. Dive operators, fishermen and resort owners have taken matters into their own hands, removing crown of thorns starfish (COTS) whenever they see them at their snorkel, dive and fishing sites. The starfish are a topic of discussion in schools, and among the Aitutaki Council.

By returning to Aitutaki two years after our initial surveys, we have been able to document the overall extent of damage, ongoing coral mortality, movement patterns of the starfish and early patterns of coral recovery. Although we never expected to expend so much effort to collect 300 COTS, we are confident that we successfully removed at least 95% of the starfish remaining on the island.

What was most unexpected was that the drove of starfish had moved from the outer reef into the lagoon. The animals continued to damage the reefs, but they occurred singly and in small aggregations, spreading out over a much larger area. We identified a single small outbreak in a back reef environment in the southeast.

High coral cover in Aitutaki’s lagoon before the COTS outbreak.

A few widely dispersed starfish still occurred on the outer reefs, but after long-distance (300-500 meter) swims by our team of four, we never found more than 4-5 animals at a time. What was most disconcerting, was that these outer reefs completely lacked the preferred species of corals, except for recruits and small juveniles, and the remaining starfish were targeting these corals. The way we found these animals was to search for any white corals. Once we found one recently eaten coral, there would be a path of dead corals extending for 20-30 m in some cases, until we came upon the starfish.

A path of destruction: Lesions from COTS on juvenile corals of Aitutaki’s fore reef.

Sadly, live coral cover on the outer reefs had been reduced from 30-80% (depending on depth) to 1-2% or less. The only exceptions were some of the deeper areas that contained species the starfish rarely ate (Porites rus), and a few larger colonies of Pocillopora eydouxi, digitate acroporids and about 30% of the larger Porites lobata. They tend to eat the species of cauliflower coral (Pocillopora) and branching acroporids that have small branches, because it is easy for them to extend their stomach around these corals, but the corals with longer and larger, more closely spaced branches were harder to eat and often they only consumed the branch tips.

Pocillopora eydouxi (left) is rarely eaten — but when it is, COTS typically consume only the branch tips (right).

What we couldn’t explain was a beautiful patch of shallow reef habitat (1-5 m) on the southeast corner that was largely undisturbed. All of the coral to the north and west of this was eaten at these depths, and there was a clear demarcation of dead coral below this patch. This is the area that tends to have the strongest wave action, and we know from other areas that the starfish tend to avoid the shallow exposed reef crest habitats.

Our surveys also provide useful information on the numbers and types of corals that have settled onto the reef since the starfish moved through the system. While we found few juvenile corals on the west and southern reefs, the shallow (3-10 m depth) fore reef at the northeastern end was quickly recovering, with densities of 10-20 juvenile corals per square meter in some locations. These included most of the species that were present before the starfish denuded the reef.

Massive recruitment of corals.

During the second week of our research, we focused on the lagoonal and back reef habitats, wading through the shallows and snorkeling among the reef framework. The most unusual observation, and one thing that made our removal efforts even more challenging, was the spread of the starfish into the lagoon.

Lagoonal habitats occupied by coral and COTS.

Extensive shallow back reef and lagoonal patch reefs and coral bommies occur throughout the western side of the atoll, extending in a band 1-1.5 km wide from the northern tip to the southwestern point. When we snorkeled on these in 2013, most of this habitat had a lot of living coral and very little algae. Now, many of the large bommies were mostly dead, and some of the larger corals were subdivided into small areas of living coral and numerous patches of white, recently killed skeleton. Plus, they were carpeted in dense mats of turf algae and macroalgae. We would find dozens of starfish in each section of the back reef we searched, but it would take 2-3 hours to carefully search an area the size of a football field.

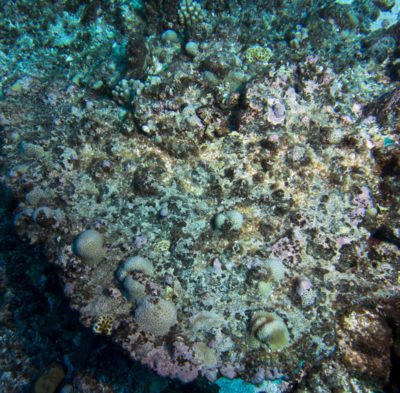

Destroyed Astreopora in the lagoon.

There are numerous bommies and reticulated reef structures at the southern end of the lagoon, but these tended to have few starfish, except in back reef areas, closer to the reef crest and fore reef. The most beautiful coral reefs we found within the lagoon was at the southeastern end. Most of the coral was still alive, consisting of dense stands of table acroporids intermixed with large bommies of Porites, faviids, Lobophyllia, Acropora, Pocillopora and other species. This area was also the location of the largest remaining outbreak. We removed approximately 150 starfish from this habitat, returning three times to ensure that we had collected all of the starfish from this area.

A shallow spur and groove reef dead on the south coast.

Addressing COTS is a demanding and somewhat frustrating undertaking, but in certain circumstances it can be successful. There are still many conservation groups and scientists that feel humans should not manipulate the ecosystem, believing that these outbreaks are natural. I’m not so sure this is the case anymore. While outbreaks have been known to occur for many decades, we are starting to understand the causes of these outbreaks, and in many cases they appear to be related to human activities – such as the input of too many nutrients from sewage and agricultural run-off.

There is also a lot of debate on the method to control the starfish. Some groups inject the starfish with poisons which are harmful to the oceans, while others have success injecting them with less noxious chemicals and compounds such as bile salts and sodium bisulfate. Some groups believe that direct collection and removal from the reef is the best option. This is certainly the least costly and low tech approach, but you must be careful that you remove them quickly and don’t injure them as they could spawn if collection occurs during the breeding season.

Finally, there is the question of whether removal efforts can make a difference. Beginning back in the 1960s, large scale removal efforts involving hundreds of thousands of animals were undertaken in Japan and other locations. After investing huge amounts of financial resources and effort, it was concluded that the effort was not successful. At the opposite end of the spectrum, for small island nations and individual reef systems and atolls, I believe we can make a difference. It is possible to collect most of the animals and save the limited coral reef resources that are present. One such example of a success, is Aitutaki.

In Aitutaki, the starfish caused considerable damage, but some of the coral remains intact. For now, Aitutaki’s reefs are out of danger and the reefs are beginning to rebound.

Photos by Andy Bruckner