Ryann Rossi is a Ph.D. Candidate at North Carolina State University who studies mangrove disease in The Bahamas. She has partnered with KSLOF to incorporate her research on mangrove disease into our Mangrove Education & Restoration Program. The following is a summary of the research she and her collaborators have done to date.

Ryann Rossi is a Ph.D. Candidate at North Carolina State University who studies mangrove disease in The Bahamas. She has partnered with KSLOF to incorporate her research on mangrove disease into our Mangrove Education & Restoration Program. The following is a summary of the research she and her collaborators have done to date.

Mangrove Education and Restoration Blog

Mangrove ecosystems are important coastal habitats. They protect inland areas from storms by breaking waves and capturing sediment. Mangrove creeks also provide excellent habitat for many important species we rely on for food and recreation, such as Nassau Grouper, Spiny Lobster, and Bonefish. Loss of mangrove ecosystems is detrimental for humans and marine species that rely on them. There are many factors, both abiotic (salinity, hydrology) and biotic (insect grazing, disease) that may contribute to mangrove die-off.

Human impacts are often cited as the most likely cause of mangrove loss. However, we have found some locations of mangrove loss that do not seem to be the result of direct human impacts such as development. Instead, we noticed that mangroves were subjected to plant disease and what appeared to be insect grazing. We wanted to know the importance of insects and plant disease in this mangrove die-off and whether they might interact. To find this out, we designed two experiments.

The die-off we have been studying is located on Abaco Island in The Bahamas in a location known as The Marls (indicated by star), the same island KSLOF runs their Bahamas Awareness of Mangroves (B.A.M.) mangrove education and restoration program.

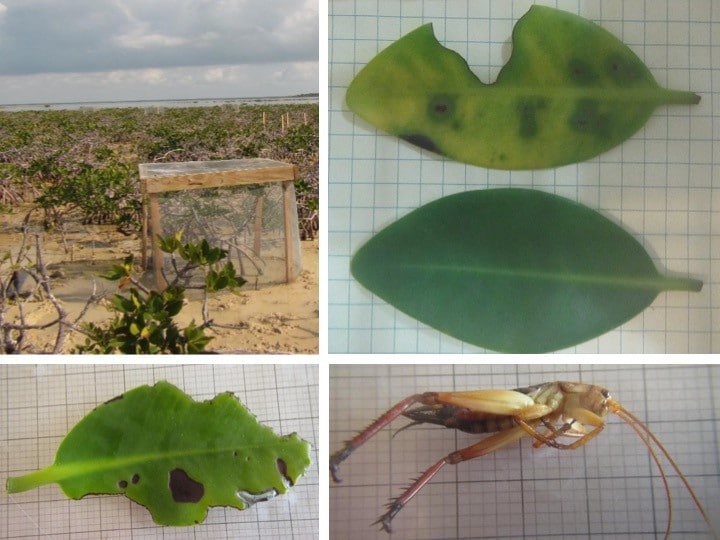

First, we designed an experiment to test how important insects were in the mangrove die-off. We put cages around single mangrove trees to exclude large insects such as crickets. From this experiment, we found that insects alone do not play a big role in mangrove die-off. Next, we set up an experiment to investigate whether there was an interaction between plant disease and insect grazing. To do this, we mimicked grazed leaves using scissors and recorded the development of lesions over a 28-day period. We found that mimicked grazed leaves had more leaf area covered by lesions than control leaves suggesting that disease and insect grazing may interact in the die-off area.

Top panel: Image of insect exclusion experiment cage and image of mimicked grazed leaf next to control leaf. Bottom panel: Image of a disease leaf and a cricket known to consume mangrove leaves.

To determine the importance of disease in the die-off, we have done surveys across the island to determine disease incidence while also collecting leaves to perform DNA analysis and grow the pathogen in culture. So far, we know that the pathogen is a fungus and we suspect it is a species of Pestalotiopsis fungi. To confirm this, we need to collect more samples and perform experiments in the lab to confirm that the fungus does cause disease.

By partnering with KSLOF, we will be able to collect more samples to confirm what is causing disease. Students in The Bahamas and Jamaica will perform disease surveys in mangroves and will also learn common techniques in plant pathology such as isolating fungi from diseased leaves and growing them in culture. These activities will provide new data regarding pathogens in mangroves and will be used to help confirm the species of fungi we suspect is the pathogen. At the same time, these activities will support teaching STEM while also creating awareness about mangroves and threats posed to them.