Fact Friday

The Galapagos is home to many unique species. Galapagos batfish have two sets of modified fins so they can walk along the ocean floor. They also have a retractable appendage on their snout that they can use like a fisherman’s lure.

Photo Credit: Iliana Baums

CORAL ANATOMY

All living things have a specific anatomy. Anatomy stems from the Greek words:

ana tomia

up cutting

Anatomy means to cut up. The word is defined as the study of the body including cells, tissue, organs, and systems. In order to study body structures, one must cut up the organism.

In this unit on coral anatomy, we are going to learn about some of the characteristics and structures of corals, and how they function.

We have discovered that corals are animals that reside in the Phylum Cnidaria. They are considered invertebrates. What is an invertebrate? Invertebrates are animals that do not have a spinal column or backbone.

Fun fact

Fun Fact

One of the most deadly animals in the world is classified in the Phylum Cnidaria – Chironex fleckeri or the box jellyfish. Its venom is said to be among the most deadly in the world!

Profile:

- Distribution: Waters around the Indo-Pacific and Northern Australia

- Size: Can reach 10 feet (3 meters) in length, including tentacles

- Life Span: Less than 1 year

- Diet: Plankton, small fish, invertebrates like shrimp

- Predators: Sea turtles, who are unaffected by the sting of these jellyfish.

- Other names: Sea wasps or marine stingers

- Special Traits: Unlike other jellyfish who just drift with the currents, box jellyfish can swim; they can see, as they have clusters of eyes

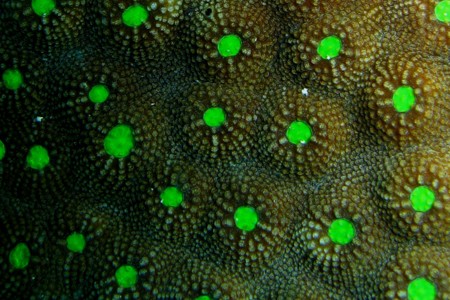

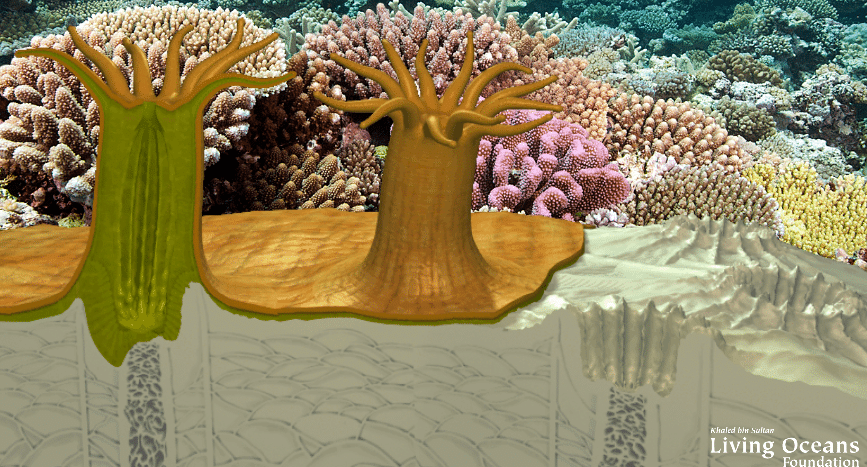

In Unit 2: Classification, we learned that organisms in the Phylum Cnidaria can have one of two body forms: medusa or polyp. Corals have a polyp body form (figure 3-1). Often coral polyps live in colonies where there are hundreds to thousands of polyps present. However, there are solitary corals as well.

Figure 3-1. Photos of different colonial coral polyps where each circle is an individual animal.

Photo Credits: a) Khaled Al-Shaikh; b) Andrew Bruckner; c) Ken Marks

Let’s take a look at a mushroom coral (figure 3-2a). This coral is one giant polyp that can grow up to 20 inches (50 centimeters) or more in diameter. Now let’s look at a brain coral (figure 3-2b). There are thousands of colonial polyps on this one coral. Each polyp may range from just millimeters in size to around 4 inches (10 centimeters) in diameter. Needless to say, in any given coral, polyps come in different quantities and sizes.

Figure 3-2. a) Solitary mushroom coral; b) Colonial brain coral containing hundreds of coral polyps

Photo Credit: Alexandra Dempsey

Use the interactive program to learn and explore more about the anatomy of a stony coral polyp. (*NOTE: This interactive may not work on Safari browsers. For best performance, try it on Chrome or another browser.)

FORM FITS FUNCTION

Have you ever heard of form fits function? It means that organisms and/or their structures are designed to perform a particular function(s). Let’s take a closer look at a coral polyp. Most corals are sessile meaning they can’t move, so they can’t actively travel to find prey. Do you think it’s appropriate that tentacles fit the saying form fits function?

The answer is yes. Unless a coral polyp has an elastic, expandable mouth, it’s not going to be able to use its tiny mouth to catch prey without its tentacles.

Let’s look at another example. Describe the teeth and mouth of a great white shark. Large, serrated, sharp teeth arranged in multiple rows, and a large expandable jaw, right? This must be good for eating seaweed. WRONG! Great white sharks have all those large, serrated, sharp teeth to consume large marine mammals and fish. They are large fish and they need a lot of energy to survive. Seaweed isn’t going to cut it for these guys. Just like corals, the mouth on a great white shark follows form fits function.

Figure 3-4. Great white shark jaw with serrated teeth

ATTRIBUTION

Figure 3-4. By Bone Clones (Bone Clones) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], 18 November 2014 via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABC-095-Great-White-Jaw-r2-Lo.jpg.