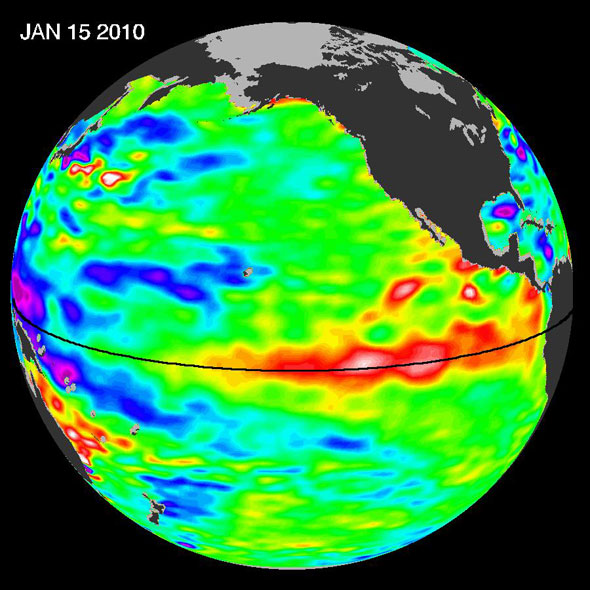

You can’t talk about coral in the Galapagos without talking about the atmospheric phenomenon called El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Normally, west-blowing trade winds push warm waters into the western Pacific Ocean. Every four or five years on average, though, the trade winds die down, or even reverse, and these warm waters move east as far as the west coast of South America, raising water temperatures as much as 7 to 10 degrees C.

ENSO can last anywhere from nine months to two years—usually about a year and a half—but while it does, it affects weather around the world, and especially around the Galapagos. The phenomenon was called El Niño (“The Child” in Spanish) because it usually starts around Christmas. It’s considered to be linked to global warming, since it has been happening more often and with more drastic results as global temperatures have risen, but the root causes are still unclear.

As the temperature of the air and water change, so do weather patterns. Warm water helps build thunderstorms, so El Niño brings more rainfall to the eastern Pacific and the west coast of South America. On the other side of the Pacific, it causes droughts in Southeast Asia and northern Australia, as well as fewer and less powerful cyclones. Overall it can raise or lower global temperatures by almost 0.2 degrees C.

Off the coast of South America, the influx of warmer waters keeps the Humboldt Current from doing its crucial upwelling. This disrupts the entire food chain: phytoplankton decrease, fish either starve or go elsewhere to find food, and so on up the ladder. In the Galapagos, these effects can be catastrophic: young birds and animals die – from flightless cormorants and Galapagos penguins to marine iguanas and sea lions. (Land plants, on the other hand, love the extra water.)

Corals, of course, are especially vulnerable to even small changes in water temperature. So, it’s sadly ironic how the recent discovery of corals in the Galapagos came just before one of the worst El Niño seasons in living memory. In the early 1980s, scientists like Gerard Wellington, Chuck Birkeland, John Wells and Peter Glynn (who is on this expedition) announced the discovery of multiple coral communities throughout the islands. Then, the unusually strong 1982/83 El Niño event raised water temperatures from the low 20s- into the 30s-degrees Celsius, which by some estimates killed up to 95% of some kinds of corals. The 1997/98 El Niño was also bad, though not as bad as ‘82/83.

The Galapagos corals have recovered somewhat since then, especially around Wolf and Darwin, but there is obviously a long way to go. On the positive side, the Islands’ normal situation (a mix of warm and cold currents), plus the periodic effects of El Niño and its cold-water counterpart, La Niña (essentially the reverse of El Niño), makes the Galapagos one of the best places in the world to study how coral communities react and recover from thermal stress. In respect to global warming, this knowledge will be essential to protecting corals and reefs around the world.

(Photos/Images by: 1 NASA, 2 Brian Beck, 3 Sam Purkis)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.