Climate change is affecting oceans globally, but many believe coral reefs are the world’s “canary in the coal mine” when it comes to irreversible damage resulting from climate impacts.

To understand the mechanisms of climate change, it is important to look at the history of carbon emissions. In the 1880s, the industrial revolution catalyzed the use of carbon-based fuel and helped advance human civilization in ways very few could imagine. However, one downside to this advancement was the exponential release and trapping of carbon in our atmosphere, usually in the form of carbon dioxide. For the past 140 years, this accumulation has resulted in substantial changes to the Earth’s climate.

The Earth’s ocean is a net carbon sink, meaning it absorbs more carbon than it releases. Within the ocean, there are many chemical changes that can occur as the amount of carbon dioxide is dissolved into the water. One of the most common changes is a decrease in the ocean’s pH as it becomes more acidic as more CO2 is absorbed, a term commonly referred to as ocean acidification (OA). This decrease in pH has led to numerous physiological problems in marine animals, particularly calcifying organisms like those found on coral reefs.

Dr. Ian Enochs heads out to take OA measurements on the Global Reef Expedition. ©Michele Westmorland/iLCP

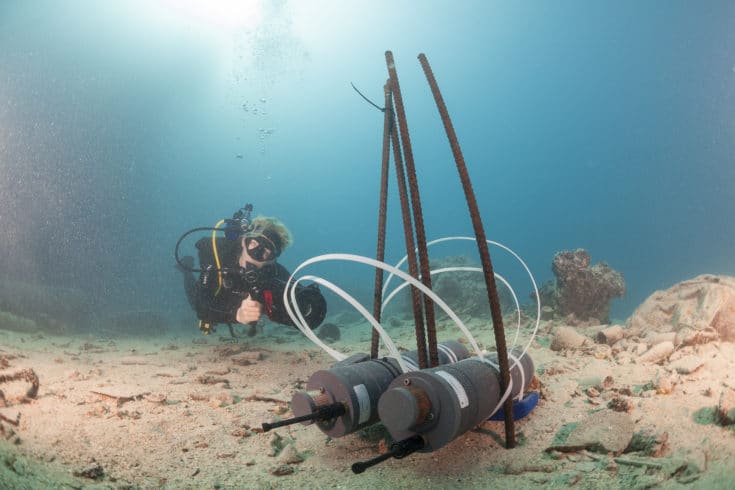

Equipment is placed on the seafloor to measure OA on the Global Reef Expedition. ©Michele Westmorland/iLCP

Calcifying organisms include animals like shellfish (crabs, shrimp, and lobsters), oysters, mussels, and corals, all important animals found on coral reefs. These organisms use carbonate, freely found in seawater, to create their calcium carbonate skeletons. When an increase in carbon dioxide is introduced into the water as a result of climate change, a chemical reaction occurs, reducing the amount of carbonate available for these organisms to use. This results in a weaker skeleton. In the case of corals specifically, this can mean they are more susceptible to breakage, dissolution, and boring animals. Since corals are reef-building organisms and the backbone of a coral reef, a strong skeleton is important for their success.

On the Global Reef Expedition, we teamed up with partners from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to assess the impacts of ocean acidification on coral reefs. We found that areas of high coral cover are actually boosting OA by making the water more acidic through respiration, and the magnitude and exposure to lower pH levels may actually be greatest on reefs with the most coral. This implies that even the healthiest reefs may face a more substantial impact from climate change, particularly OA, if nothing is done to address this problem.

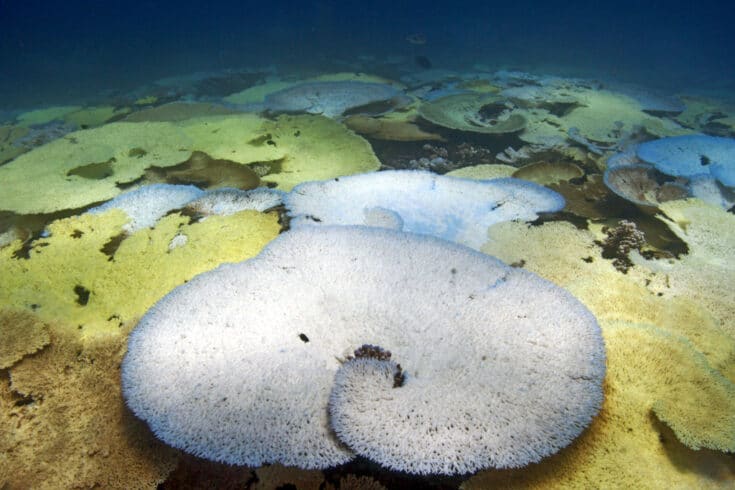

Bleached anemones on the reef in the Chagos Archipelago.

Renée Carlton swims across a bleaching reef in the Chagos Archipelago.

Corals changed color in the process of bleaching in Chagos.

A reef in the process of bleaching in Chagos.

Corals in the process of bleaching in the Chagos Archipelago.

As the ocean becomes more acidic, carbon emissions trapped in our atmosphere are also causing the climate—and as a result, our ocean—to warm. Coral is highly susceptible to temperature changes, and prolonged warming events have led to numerous global bleaching events since the time of our surveys on the Global Reef Expedition. In fact, at our last research site, the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, we were the first to witness what would become one of the worst bleaching events on record. Surveys that took place a year after our surveys showed live coral cover was reduced to 5-15%.

Climate change is a complex issue, and coral bleaching and ocean acidification are just two problems that can substantially damage coral reefs. Without a rapid response to climate change, the reefs, and the lives of the millions of people who rely upon them, will be drastically altered.

Global Reef Expedition Final Report

Learn more in the Global Reef Expedition Final Report. Over the course of ten years, the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation circumnavigated the globe studying the health and resiliency of coral reefs. This report summarizes our findings from that research mission, provides valuable baseline data on the status of the world’s reefs at a critical point in time, and offers key insights into how to save coral reefs in a rapidly changing world.