We began our research dives with two spots on the Atlantic side of the St. Kitts and Nevis coral reefs, seaward of the narrows in a reef system known as Grid Iron. This shallow reef stretches over 10 km from the northeastern end of Nevis to the coastline off St. Kitts. Formerly a flourishing elkhorn coral reef at depths of 5-10 m, most of this coral died 30 years ago and dense interdigitated skeletons remain in growth position. We did find a few survivors, some growing atop old skeletons and others sending branches up from the bottom.

St. Kitts and Nevis Coral Reefs

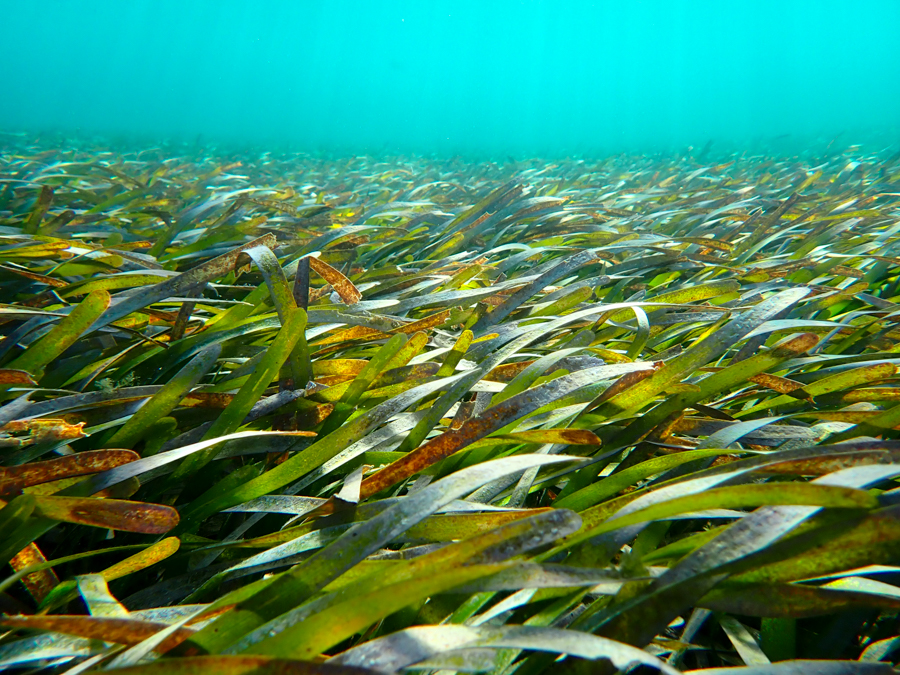

At the perimeter of the elkhorn coral thicket were unusually large (3-5 m diameter) colonies of lobate star coral (Montastraea annularis) and mountainous star coral (Montastraea faveolata). Many of these had also had died, although a large number of the colonies still had small patches of live tissue on the topside of the lobe. In some cases, these tissue remnants were actively resheeting over the skeletons and continuing their upward growth, resembling a juvenile coral. Large brain corals had suffered similar fate; many standing dead in place, others with small living tissue remnants dispersed over the colony surface. However, a closer inspection of the reef revealed many signs of recovery. A dozen species of coral had settled on the dead skeletons and were expanding outward. While most of these were species that tend to be early colonizers and short-lived, such as mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides), we also saw a number of more long-lived massive corals like starlet coral (Siderastrea siderea) and brain corals (Diploria spp. and Colpophyllia natans). A lot of the bottom was covered with fleshy seaweeds or macroalgae, especially a bushy brown macroalgae known as Dictyota. Underneath this alga, and also commonly seen covering dead coral heads was bright pink crustose coralline algae, which is a good sign as this is known to be preferred settlement surface for larval corals.

Large fish were notably absent, but there were many smaller herbivores, including juvenile parrotfish and surgeonfish, which were actively grazing on the algae.

The St. Kitts and Nevis coral reefs also had a few long-spined black sea urchins, another keystone herbivore known to control algal populations.

Our afternoon dive was off the southwestern tip of St. Kitts at Nags Head. This reef extends from just below the water’s surface to 70-80 feet. Large volcanic boulders that have fallen from the surrounding cliffs form a mini-wall, with small caves, crevices and channels between the rocks. Much of the bottom was covered in fine silt, with a lot of fleshy macroalgae and cyanobacteria, but the coral community was quite unusual and diverse. Corals normally seen in deep water, including large plates of sheet coral (Agaricia lamarcki and A. grahamae) and cactus coral (Mycetophyllia aliciae), carpeted the vertical surfaces of boulders. Other corals that form boulders in shallow water exhibited plating growth forms in response to lower light levels and turbid conditions. Competing for space with the corals, sponges every color of the rainbow grew into barrel shapes, tubes, twisted ropes, and baseball-shaped lobes. What was most interesting was the high numbers of small corals, recruits and juveniles that had colonized the volcanic rocks.

In addition to brain corals, star corals, starlet corals, finger corals and other common species, mountainous star coral (Montastraea faveolata) colonies formed small sheets and volcano-shaped mounds. This coral is one of the most important reef-building corals in the Caribbean, but over the last 15 years it has suffered large die-offs from bleaching and disease. Juvenile colonies are also rarely seen on a reef, as larvae rarely settle and survive.

Our first full day of research at St. Kitts and Nevis coral reefs was extremely productive. Our core team characterized three reefs, completing several dozen benthic transects, coral transects and fish transects. Simultaneously, our local divers got more experience in coral reef assessments and began to collect meaningful information on the status of their coral reefs.

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and our team members.

(Images/Photos: 1-5. Andy Bruckner, 6. Amanda Williams)