Even though we are in a very remote location off the southern Red Sea coast of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, fishermen abound. There are many coastal villages near the Farasan Banks with large fishing communities. Many of our sites are 50 miles or more offshore, and as we approach a reef we see small fiberglass fishing boats. Sometimes they fish in pairs, but it’s often a single boat with two fishermen.

The coastline bordering the Red Sea represents about 79% of the total Saudi coast, yet fish production from this area is reported to be only about 50% of the total production. The industrial fleet, which we have not seen in this area, uses mostly trawl nets to target demersal fish stocks and shrimp. Most of these vessels are owned by the Saudi Fisheries Company, and they operate out of Jizan, south of the Farasan Banks. In areas further north of Jeddah, such as the Wajh Bank area that we examined last year, fish traps dominate the artisanal fisheries. We saw fish traps in reef habitats, often placed on top of coral and also next to the reef. These traps are locally known as “gargoor”.

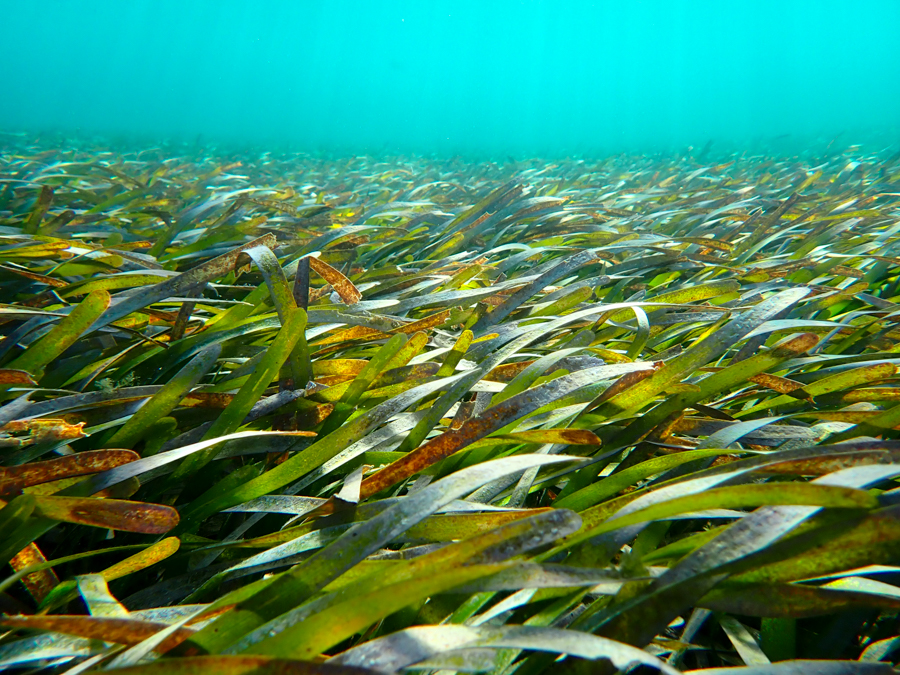

A derelict net covering the reef.

Fish traps are used less frequently in the Farasan Banks. In fact, I have yet to see a fish trap on a dive. Rather, the fishermen use handlines, gill nets and small trawl nets. Most of the fishermen appear to target reef and small pelagic fish, just off islands, shallow reefs and banks.

While Saudi citizens own and operate traditional and industrial vessels, most of the fishers were expatriate workers, often from Bangladesh and sometimes India.

On one shallow inshore dive, I found a large net wrapped around numerous coral heads. This is a typical wall net (with relatively large openings) that fishermen use to catch large herbivorous fish that they cannot hook on handlines, such as parrot fish. These nets may also be used to catch transient reef predators, such as trevally and dogfin tuna. This may be done by chumming or baiting an area close to the reef, then enclosing it with the net so the fish are caught between the reef and the net with nowhere to escape. This type of net is what is also most commonly used in the Harid Festival in Farasan Islands.

Yesterday we dove a very interesting horseshoe shaped reef about 40 miles offshore, with vertical walls dropping to 500 meters on all sides. Eight fishing boats were targeting reef fish near the entrance to the lagoon.

Coming in close to the reef flat, we approached a fishing vessel to learn a bit more about their catch. The two fishermen were using live fusiliers (Caesio striatus) as bait, which were caught using a cast net. Hundreds of these striated fusiliers were swimming around in a live bait well in the middle of their boat. These sleek, silvery fish have forked tails and swim in large schools above the reef, feeding on plankton.

In about a half hour of fishing, they had caught six fish on handlines; a lunartail grouper (Vaiola louti), redmouth grouper (Aethalaperca rogaa), 2 Carangid jacks, and 2 mackeral species. Their catch was kept in a holding tank on ice.

The two fishers had been away for four days, camping on a nearby island every night. It amazes me that they come so far offshore in such a small (but seaworthy) fiberglass boat. The boat was only about 4m in length, equipped with a 60hp engine and had no navigation equipment.

While the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has closed seasons for grouper, mesh size restrictions for gill nets and several marine protected areas, many reefs appear to have few large predators, even in the remote reef habitats surrounding the Farasan Banks. Currently, they still catch groupers, snappers and many larger pelagic species, but they also target herbivores and other fishes. Life for these fishermen does not seem to be easy or comfortable, and it’s probably getting harder to make a living each day. Hopefully, our work here will contribute to the development of expanded conservation measures that lead to rebuilding of fish stocks, so they can continue to glean an income and food from the sea.

To learn more about Red Sea fisheries, continue reading some of the interesting facts provided by our fish experts, Ameer Abdulla and Hussain Al Nazry:

Red Sea fish have a long history in marine science and taxonomy. In 1760, Peter Forskaal (a student of Carl Linneas, the founder of modern taxonomy) sailed from Egypt to Yemen on a scientific expedition to document and study the natural history of the Red Sea. Forskaal died of malaria in Yemen in 1763. Of the 155 species of fish that he named, he used the Arabic name for 43. Some of these fish include Abudufduf, Letherinus mahsena, Hiposcarus harid, Lutjanus kasmira, and Variola louti.

The southern Red Sea, including the Farasan Banks and Farasan Islands region in Saudi Arabia and the Dahlak Archepalago in Eriteria, has the highest productivity of fisheries in the entire Red Sea. This rich fishery is a result of the high nutrient content of these waters, which increases the amount of phytoplankton and zooplankton (secondary productivity) available in the foodweb. High nutrients are driven mainly by the broad and relatively shallow shelf which facilities resuspension of nutrient-laden sediment and the inflow of nutrient rich surface water originating from upwelling areas in the Gulf of Aden.

As of 2005, traditional practices still account for the majority of fishing methods in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea at 68%, while the industrial fishery accounts for only 32% of all fishing. Traditional fishing is mostly (92%) undertaken by handline and gill nets with pot traps accounting for only 6% of methods. The major fish groups caught, in order of importance, are: groupers, trevallies, emperors, mackerel, barracuda, snapper, tuna, shark, and parrotfish. The most important and productive fishing is Jazan, yielding approximately 7599 metric tons of marine fish.