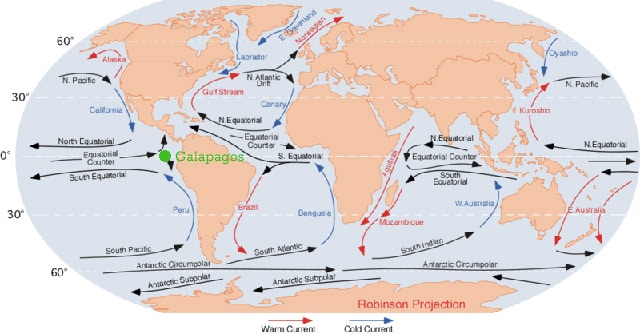

Why are the waters around the Galapagos Islands so rich with marine life? It’s because the islands are in a very special spot. Oceanographically speaking, they are at the intersection of five major ocean currents. Along with the equatorial surface weather, these ocean currents help dictate the islands’ climate and their unique ecology, both above and below the water.

Ever since man has been coming to the Galapagos, we’ve been struck by how mild the climate is for being right on the equator. Charles Darwin wrote how surprisingly un-tropical the weather was, stating, “[It] is far from being excessively hot…excepting during one short season, very little rain falls, and even then it is irregular.” Being a genius, he also pinpointed the main reason, “[T]his seems chiefly caused by the singularly low temperature of the surrounding water, brought here by the great southern Polar current.”

Galapagos: Where Ocean Currents Meet

Now called the Humboldt Current, after the 19th century European explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, this most massive of ocean currents sweeps north up the western edge of South America. It carries cold, nutrient-rich water from Antarctica along the coasts of Chile and Peru, creating the world’s most productive marine ecosystem in the process. (It also brings animals; that’s how penguins and fur seals first reached the Galapagos.)

At the equator, the Humboldt turns west, helped by the Earth’s rotation and seasonal winds, and joins the South Equatorial Current before heading straight toward the Galapagos. The cool waters of these ocean currents help keep the islands’ climate mild, especially in the summer and fall. Right now, we’re at the start of this “dry season,” marked by generally cloudy skies, cooler temperatures and misty rain in the highlands called garúa.

Around November, the “wet season” starts as warmer waters arrive from the northeast via the Panama Current, which flows down from Central America. This current isn’t nearly as rich in nutrients as the Humboldt, but it does make for warmer diving with better visibility, as well as sunnier skies and an explosion of green on land.

That’s three ocean currents so far. Then, in between the South Equatorial Current and its northern counterpart (too far north to directly affect the islands), the wind-driven North Equatorial Countercurrent flows from west to east, threading the needle between the two westward-flowing Equatorial Currents.

Lastly, and possibly most importantly, is the Cromwell Current, aka the Pacific Equatorial Undercurrent. Until now, we’ve been talking about surface ocean currents, but the Cromwell flows about 300 feet down, from west to east along the equator. When it hits the Galapagos from the west, it’s deflected toward the surface, bringing yet more cool, nutrient-rich water.

Does that sound familiar? Like the Humboldt, the Cromwell Current offers an example of upwelling. As ocean organisms die, they sink and decompose into their component parts. Whenever the cold water that holds these nutrients is brought to the surface, it stimulates the growth of microscopic organisms called phytoplankton, the base of the oceanic food chain. Like plants, phytoplankton photosynthesize sunlight, so they stay near the surface. More phytoplankton means more marine life, and lots of phytoplankton means a living aquarium like the Galapagos.

For a more visual representation of ocean currents, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center created a time-lapse computer model called Perpetual Ocean.

(Photos/Images by: 1 Wikipedia, 2-3 Josh Feingold)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.

2 Comments on “Galapagos Ocean Currents”

Batman

jamsedsns sucks

hamgurber

SPIDERMAN

this article straight gas fs, bru got all his facts straight.