After a night boarding at Errol Flynn Marina at Port Antonio, Jamaica and a rolling crossing that left more than a few green faces and empty chairs at dinner, the Golden Shadow motored overnight to Pedro Bank, about 100 miles southwest of Kingston.

Now we’re anchored off Southwest Cay, a.k.a. Bird Cay, one of four small, mostly empty islets that together cover a tenth of a square mile. It’s a strip of sand with a few bushes and palm trees and a long, low pile of what looks like bleached coral but is actually empty conch shells discarded by fishermen over the decades. Just beyond it is Middle Cay, one of two inhabited islets, with a Jamaican Coast Guard station, a research station built by The Nature Conservancy, and a scattering of fishing huts.

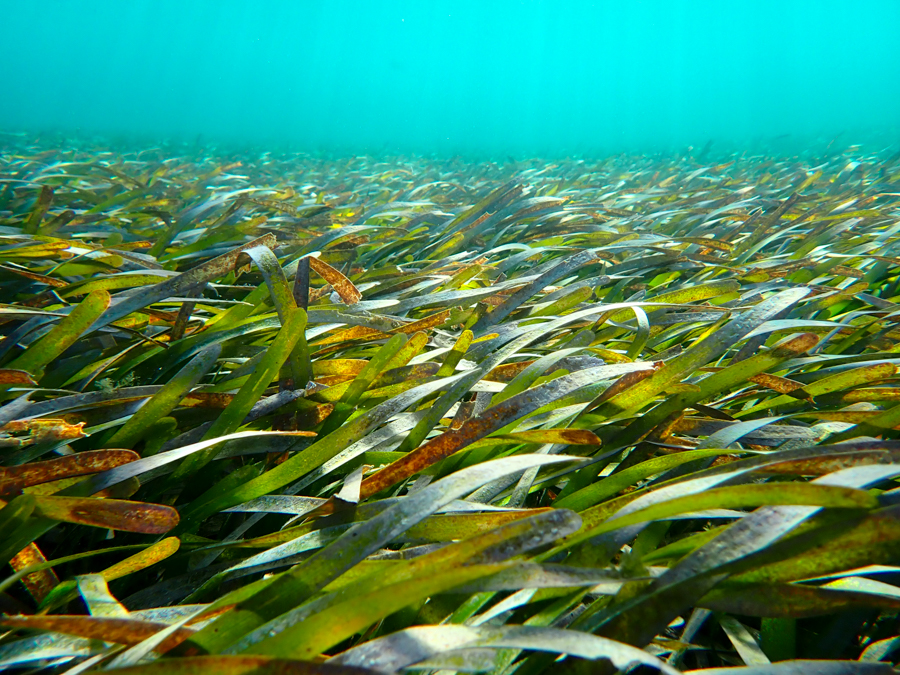

Most of Pedro Bank, though, is below the surface: a roughly triangular rise in the seafloor covered with reefs, rocks, seagrass and sand. About 2400 square km—a little less than a quarter the size of Jamaica—is 20 m deep or less. It’s home to hundreds of historic shipwrecks and, even more importantly, lots of fish and coral. Thanks to its size and isolation, the Bank is Jamaica’s most important fishing ground, with some of the country’s best-preserved reefs. Considering over 90% of Jamaica’s reefs are in danger, that makes it a critical place to protect.

Like many reefs around the world, the Bank’s coral ecosystems are threatened by things like overfishing, human pollution and the effects of global climate change. The Global Reef Expedition is here to help figure out how healthy the reefs are, what’s living there and which areas are most resistant to disturbances—and why.

Some reefs rebound from disturbances while others don’t, or at least not as quickly. One of the Expedition’s major goals is to tease out which factors make a reef resilient, eventually coming up with a resilience “score” that indicates how likely it is to recover from things like sewage run-off, invasive species and rising sea temperatures. There’s not much local fisheries managers can do about rising temperatures or other global threats, but they can manage localized impacts like overfishing and pollution. The data the Expedition collects on what makes a reef resilient can help them make these decisions.

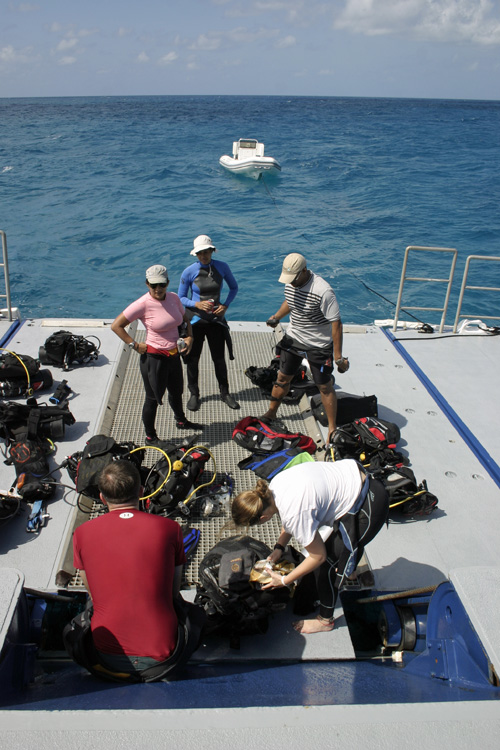

This morning, Dive Safety Officer Nick Cautin organized a “shakedown dive”. After lunch, the Calcutta dive boat took everyone out for some real work: the coral survey team, the benthic cover team (focusing on the bottom), two fish survey teams, one group looking at large mobile invertebrates like conch and lobster, another focusing on plankton communities, and finally Steve Schill of The Nature Conservancy and his fancy sidescan sonar (more on that later.) Captain Phil Renaud, Executive Director of the Living Oceans Foundation, helped with photo transects.

Everything went well on the afternoon dive, but tonight’s weather forecast isn’t promising: 25-knot winds and six-foot seas for the next five days. Just one-meter swells made it tough to get in and out of the Calcutta this afternoon. We’re keeping our fingers crossed that the weather holds.

(Photos/Images by Julian Smith)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.