Today’s guest blog comes from Riley Ames, a student at the University of Miami working on our Protist Prophet project, which uses foraminifera we collected on the Global Reef Expedition to create an index of coral reef health.

My name is Riley Ames, and I am a second-year oceanography and marine biology student at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science. I have been working in the marine geosciences laboratory studying foraminifera since 2022, and I spend most of my time outside of class in the lab. I greatly enjoy my work there; in fact, I have discovered my passion for micropaleontology through my work on benthic foraminifera. I currently work on the identification of foraminifera. Primarily, I worked on completing the New Caledonia data subset, which I finished earlier this year.

The process in our lab is a lengthy one, and there are quite a few steps in the process that occur before I ever even see the slide for identification. The sediment sample must be sorted by a student using a fine paintbrush or needle. These students must pick out 200-300 individual foraminifera and separate foraminifera from grains of sand, rock, and other microorganisms. After that, the sample is passed to yet another student, who precisely glues each foraminiferal test to a micropaleontology slide.

Over the course of my time in the laboratory, I have learned to do both of these jobs. I spent almost six months picking, and the following three months gluing. Both are challenging in different ways; picking requires nearly unlimited patience, and gluing requires extreme attention to detail.

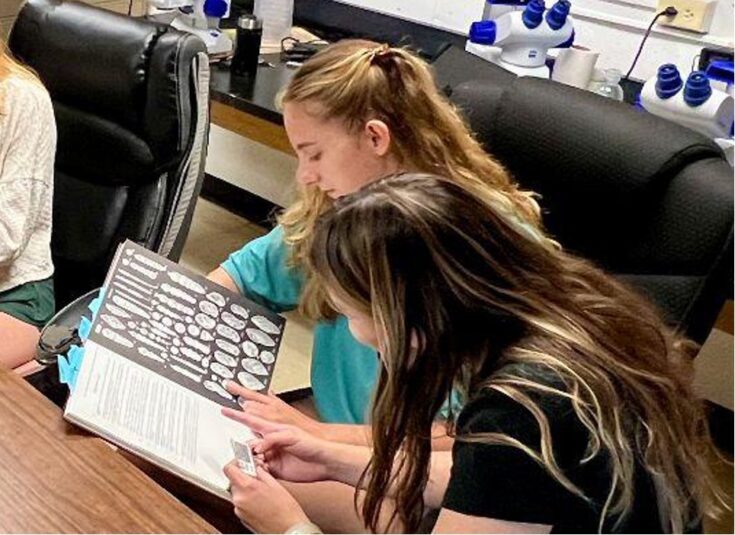

Arguably the most complicated part of our scientific process is the identification of foraminifera. This is one of the largest undertakings in the lab, and the work is incredibly complex; it takes months to be well-versed in the foraminifera of a particular location. Looking at a glued slide through a microscope, I am able to identify each foraminifera down to the level of genus. Another undergraduate research assistant (or occasionally, Dr. Humphreys, who will stand in when no students are available) will sit nearby to enter the data as I call it out.

Occasionally, I stumble upon a genus that I’ve never seen before. Usually, I will call on Dr. Humphreys or our postdoctoral scientist for their opinion. If they are unsure, I refer to guidebooks and databases. In the laboratory, we keep specialized guides for a variety of regions, as well as more generalized “foram dictionaries.” The World Foraminifera Database is another excellent resource that often helps me to identify new foraminifera. We maintain a “master slide” containing new or rare foraminifera for later reference.

The process from sediment core to large dataset is long and complex, requiring work at multiple levels. The teamwork, dedication, and patience of the researchers in this lab are extraordinary, and I cannot wait to see where this project will go in the future.