We have had many interesting dives within the lagoons around the Tuamotu Archipelago, but the Fakarava lagoonal habitats have been the most unique. There are thousands of small patch reefs that extend from the water’s surface to depths as great as 55 m. Some of these lagoon reefs have an emergent island with vegetation, while others have a small emergent sand patch with some rubble and coral boulders, and others are totally submerged. Each type is unique in structure. In cases where the top of the submerged reef is 2-3 m below the surface, there is a community dominated by unusually large boulder-like Porites, some which can be over 15 m in width. Porites corals are sometimes described as finger corals or massive corals.

As the Porites colonies grow up to sea level, the tops of the colonies are exposed during very low tides, and they die, and then become colonized by branching corals (Acropora, commonly called elkhorn, table, or staghorn corals, and Pocillopora, commonly called cauliflower or brush corals).

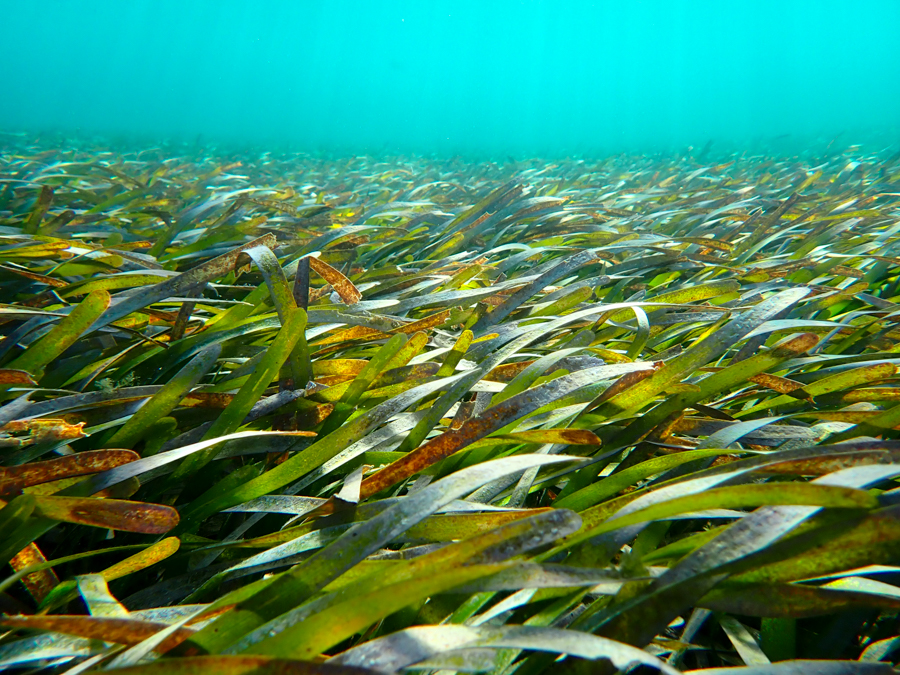

Over time, the Porites colonies continue to expand outward, towards deeper water, but the colonies in the center of these lagoon reefs die completely and are replaced by a branching coral community. Eventually, the center resembles reef flats found on the atoll’s outer rim, with dense stands of small Acropora colonies, fields of large tree-like Acropora and an outer rind of Porites colonies. The surrounding slope is very steep, composed of sand, coral rubble and boulders that break off from the rim of the reef flat. The base of these structures is comprised of accumulations of old, dead coral colonies that rolled down the slope, and is covered by woven macroalgae, known as Microdictyon.

The boulders of these lagoon reefs have very little coral growth, presumably because recruitment is inhibited by steep slopes and debris covering the slope. The water is also much more turbid in the lagoon reefs than outer reefs at the same depth due to the high photosynthesis of the benthic communities and the poor flushing of the atoll. There is, however, often a dense aggregation of finely branched, tall and spindly Acropora colonies that can survive in this environment because the wave exposure is so low and the colonies are too tall to be buried by sediments.

(Photos by: Dr. Andy Bruckner)

If you liked this blog, you might also like: Lagoon Life from our Colombia mission.