What comes to mind when thinking about a coral reef is a colorful undersea garden teaming with life: corals, fish, urchins, starfish, molluscs, crustaceans, sponges and other animals and plants, many still unknown to science. French Polynesia coral reefs should provoke similar perceptions. French Polynesia is very remote. Total human population is low. Many of the atolls are uninhabited and pressures on the reef are minimal. French Polynesia coral reefs feature vast areas of barrier reefs and fringing reefs encircling the more than 80 atolls (out of about 450 worldwide!), deep-water lagoons crowded with patch reefs, and extensive coral dominated reef flat communities (more than 6000 sq km of coral reefs). These French Polynesia coral reefs are home to more than 800 species of fish, about 170 species of corals, over 1100 species of molluscs, hundreds of other invertebrates, and 350 species of algae.

While this is far fewer than that found in the center of biodiversity, known as the coral triangle area (which includes Indonesia , the Philippines and several other surrounding countries), the composition and structure of French Polynesia coral reefs differs dramatically between high volcanic islands and atolls, and even more so within the lagoon. Some of these differences are due to physical and environmental factors, but other processes may also play a role.

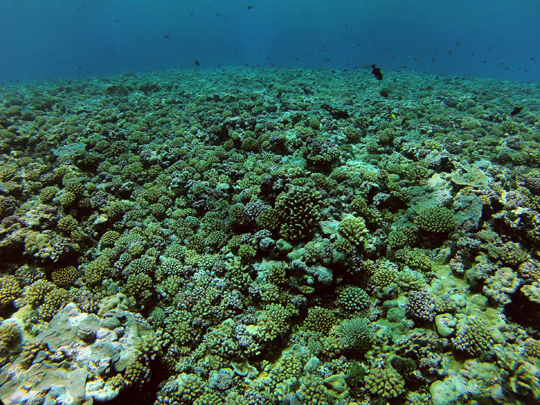

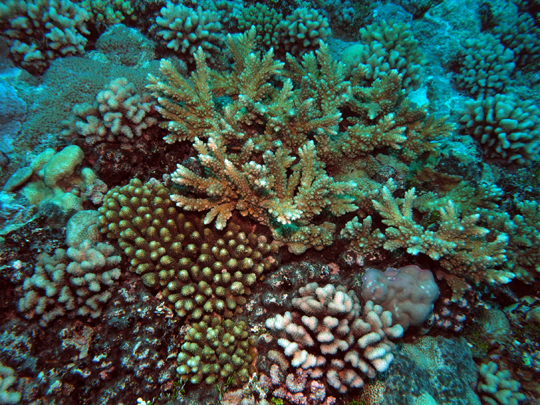

Having completed surveys around five areas of French Polynesia coral reefs, including four low-lying atolls and one steep-sloping volcanic island, one observation is that every reef is unique. Often, the dominant species of corals occurred in each location, but the abundance and health of these differed. The three most remote atolls (Mopelia, Scilly and Bellinghausen) all had flourishing coral communities on the fore reef, with live coral cover often approaching or exceeding 80% in shallow water (1-15 m depth).

Yet, deeper areas had little coral, and often many of the colonies were stark white – recently dead. What seemed unusual, though, was the size of most of the corals in shallow water on the fore reef that made up most of the living cover – generally 10-30 cm. Based on the growth rates of the most common species (the branching corals), this suggests that a large percentage of the colonies were young – perhaps 5-6 years up to about 10 years old.

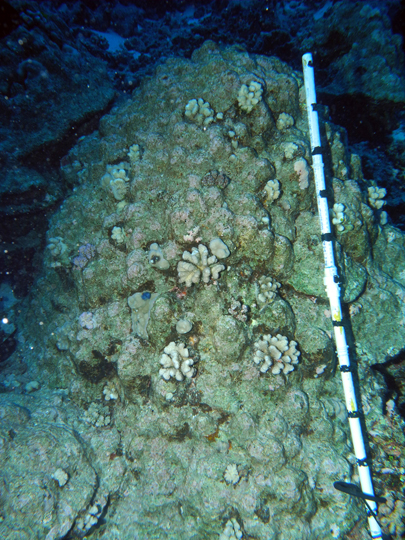

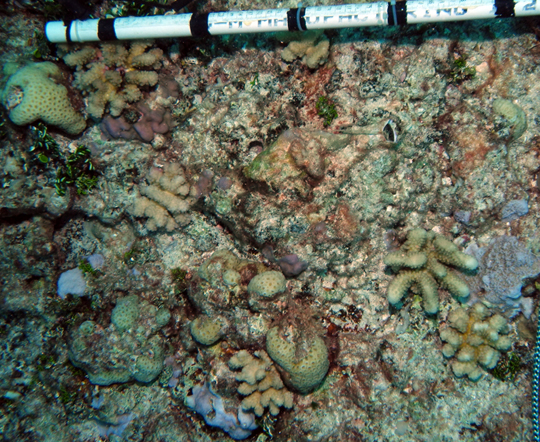

From a distance, reefs around Tupai and Huahine looked to be nearly dead from the surface to the base of the reef. Few large corals remained, thickets of branching corals that made up much of the live coral cover in the other locations were absent, and the bottom was covered in rubble (broken branches of dead coral). Upon closer examination, it was obvious that the reefs were not dead, but undergoing a rapid recovery. It was as if a forest fire had gone through the reef and burnt down the evergreen trees. What had come back were the grasses and the small bushes, or in this case, the bottom was carpeted in baby corals (sexual recruits) and juvenile corals most of which were from less than 1 cm in diameter up to about 3-4 cm.

The same dominant species – branching pocilloporids and acroporids, massive Porites and faviid corals, and plate-like and encrusting Montipora and Pavona colonies. Often, there were 20-30 new recruits per square meter, which is unusually high, especially when compared to the Caribbean. There were other positive signs, as well: high amounts of encrusting calcareous red algae and very little fleshy macroalgae, lots of small herbivorous reef fishes, and few nuisance species. By all accounts, these reefs experienced a major disturbance (or possibly many major disturbances), but they exhibit unusually high resilience; within 4-5 years they should look just like their counterparts surrounding Mopelia, Scilly, and Bellinghausen.

The first question that should come to mind is: What caused the loss of the corals? Come back tomorrow to find out more about these French Polynesia coral reefs.

(Photos by: Dr. Andy Bruckner)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.