Another long, three-dive day in the Calcutta, with more lionfish spearing and a sea turtle sighting. While almost everyone else was underwater, Steve Schill and his group—Sean Green, Junior Squire, and Azra Blythe-Mallet—were staying dry, although they were looking at the bottom in just as much detail. Based on the Twin Vee, Steve’s crew operates the brand-new Tritech Starfish sidescan sonar (990f).

It looks like a little red plastic rocket, under 38 cm (15 in) long, but costs as much as a decent used car. This kind of sensor is often used by search and rescue teams for body recoveries, and also for surveys of wrecks, canals, lakes, ports and harbors—anywhere people want to know in detail what’s under water up to 35m (114 ft) deep.

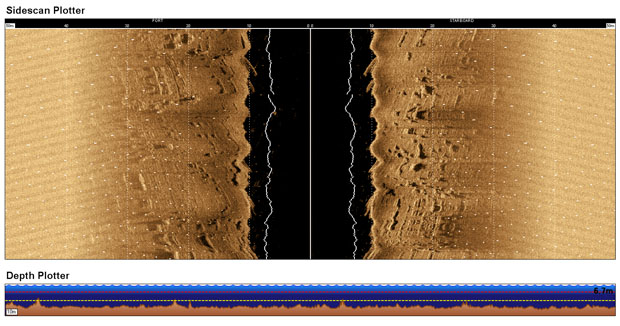

As it’s being towed underwater behind the Twin Vee, the Starfish sidescan sonar sends out “compressed high intensity radar pulses” in the 1-MHz range, down and about 30 m (99 ft) out to each side. These fan-shaped sound pulses reflect off the bottom, and anything on it, and the Starfish records how strong they are and how long they take to return. Hard materials like stone or metal reflect stronger echoes than finer materials like silt.

As the boat tows the sonar back and forth, like a lawnmower trimming a golf course, a laptop up on deck records the acoustic reflections, or “backscatter.” This continuous image of the seafloor is eventually sent off to an image-processing company, where it’s stitched together like a panoramic photo and classified according to what’s on the seafloor: sand, reef, seagrass, and so on.

The result is a map of the seafloor down to a resolution of centimeters in ideal conditions, including ripples in the sandy bottom. Schools of fish and large waves distort the images, which is why Steve had to wait a few days at first to launch. There’s also a digital “drop cam” recording video of the bottom for comparison.

On this expedition Steve’s team is sticking within about two miles of Southwest Key, the one the Golden Shadow is anchored nearest. Why? Because the Nature Conservancy has proposed the area as the first fish sanctuary in Pedro Bank, and the first step to protecting an area is knowing what’s there to protect.

Fishing will be prohibited and people will be discouraged from landing on the cay, an important nesting ground for seabirds like masked boobies and roseate terns and endangered turtle species like hawksbills and loggerheads. Combined with satellite imagery, the Starfish sidescan sonar and dropcam data will eventually help create the area’s first detailed seafloor habitat map.

In the afternoon a few of us, including the film crew, visited Middle Cay with Azra Blyth-Mallett from the Jamaican Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. Roughly 100 people live year-round on this four-hectare (10-acre) islet, with no running water and only generators for electricity. (The population can swell to 400 or 500 during Queen Conch season.)

It’s a difficult existence, but they’ve set up a small village, with streets and buildings, shops and workshops, all built out of material brought by boat from the mainland. There are two permanent buildings: a security post belonging to the Jamaica Defence Force (coast guard) and a field and research station built by The Nature Conservancy as part of their Pedro Bank Management Project.

(Photos/Images by: 1 Andrew Ross, 2-3 Julian Smith)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.