Our research team headed south for today’s dives, surveying two reefs off the southwestern end of Nevis and one off the northwestern end. The first site, Caverns, was a raised terrace with large volcanic boulders at its margin and a prominent undercut ledge that dropped into a gently sloping sand patch. Most corals were small, but unusually diverse and in excellent health. There were many pillar corals (Dendrogyra cylindrus), including flattened juvenile colonies that lacked upward spires. This coral is unusual, in that it has long tentacles that are extended in the day.

Another unusual species, the spiny flower coral (Mussa angulosa) has large fleshy polyps, spiky skeletal structures (septa) and is brightly colored shades of green and fluorescent red.

At this site we found our first colony of staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis). This species is closely related to elkhorn coral, but more bushy with circular branches that are much more narrow and have a large pronounced apical polyp. This coral once formed extensive thickets, 100s of meters long, which would provide refuge for schools of grunts and other reef fishes. These dense stands are rare today, and this species is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list.

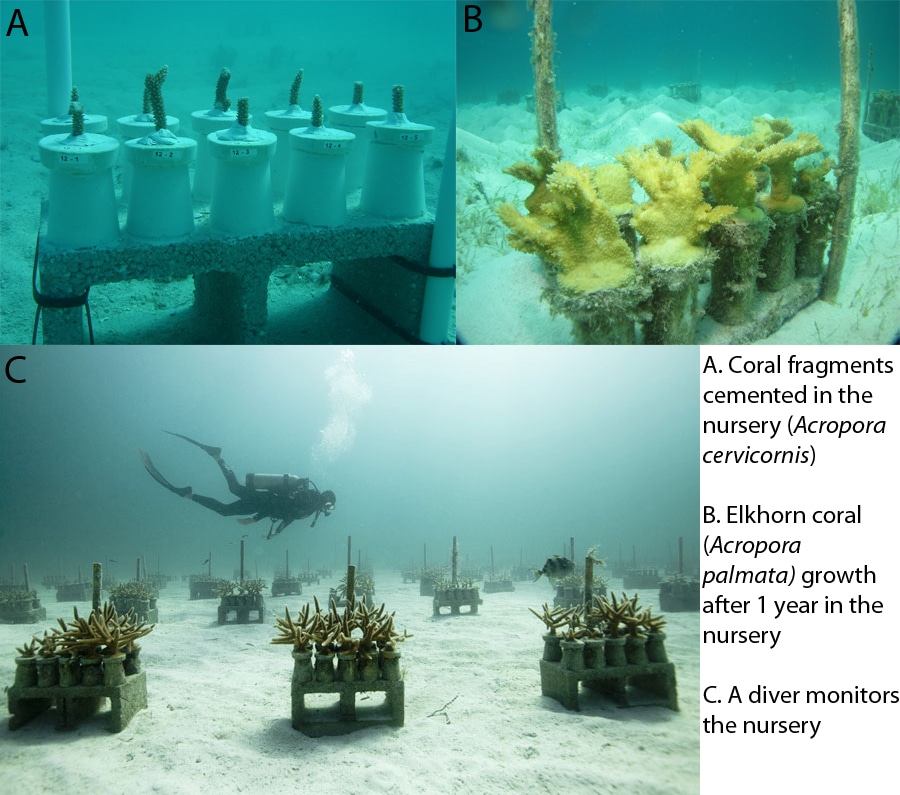

Several members of our team from the Nature Conservancy’s office in the USVI, have developed nurseries to propagate this coral from broken branches, or fragments, much like you grow a cutting from a tree. The fragments are attached to a base, or are tied onto nylon line suspended in the water column, and carefully maintained, removing algae and coral predators to keep them healthy. Unlike most other coral species, they grow very quickly (15-20 cm/year). Once these fragments grow into small bush-like colonies, they will be transplanted back onto the reef; this may serve as an effective mechanism to restore the species to its former dominance.

One of the many challenges we face each time we do our coral surveys are injuries from stinging organisms. While we have been fortunate to avoid jellyfish during this mission thus far, each of us has been hit by fire coral. It is easily seen, but difficult to avoid, especially when there is strong surge and currents. Fire coral produces a hard, stony skeleton like the reef-building scleractinian corals. These are only distant cousins, though. They are known as hydrozoan corals, while other stony corals are in the class Anthozoa. Like corals, they have batteries of stinging cells, or nematocysts, which are located in the translucent tentacles that are extended during the day and night. Unlike corals, they are much more venomous. There are three species commonly found in the Caribbean. The most common (Millepora alcicornis) often overgrow soft corals, forming a narrow, elongate branch that extends up into the water column. At Caverns, another species (Millepora complenata) was also common, forming extensive crusts on rocks and dead coral surfaces.

Our second dive was located off the southern tip of Nevis, at the shallow end of a bank that extends nearly to Montserrat. While this is one of the most important fishery areas in Nevis, the bottom is relatively flat and heavily scoured by strong waves and currents. Stony corals, sponges, soft corals and other invertebrates are found here, but they are fairly sparse and small, often forming a crust or plate in response to strong currents. Today was no exception; several of the divers were unable to get to the bottom, and those that did burned up their air fairly quickly fighting the current.

(Images/Photos: 1-3 Andy Bruckner, 4A-4B James Byrne, 4C Tim Calver, 5 Andy Bruckner)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and our team members.