Life on a coral reef in French Polynesia can be extremely unforgiving. Natural coral threats, especially cyclones, crown of thorns starfish (COTS) outbreaks and coral bleaching events, have caused severe damage. Fortunately, because of the isolation and low human population density, human impacts are relatively low, except near a few urban areas.

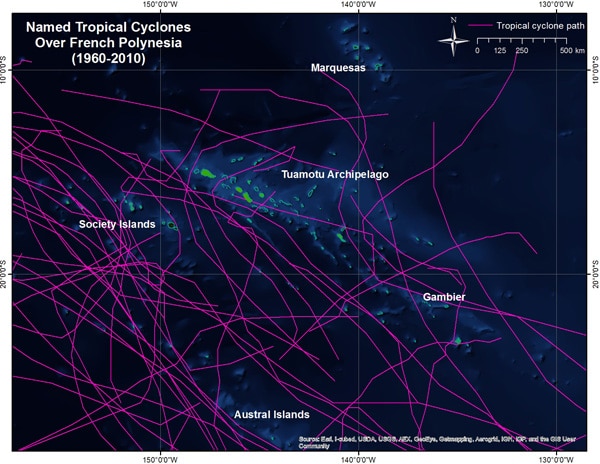

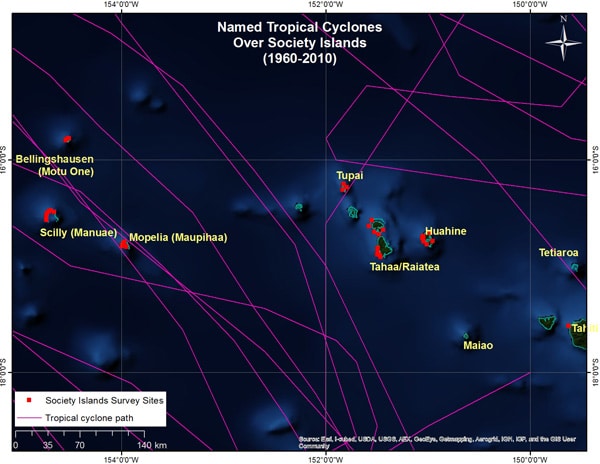

French Polynesia is located within an area of unusually strong cyclone activity, making one of the primary coral threats. For the first 80 years of the 20th century, Society Islands was not affected by a single cyclone. Shortly thereafter, in 1982, 7 major storms struck the region. Since then, there have been another 85 cyclones, mostly coming from the south. There was a lull in storm activity between 2003-2006, and then 2 cyclones hit in 2007. Most recently, Tropical Cyclone Oli hit French Polynesia on February 3, 2010.

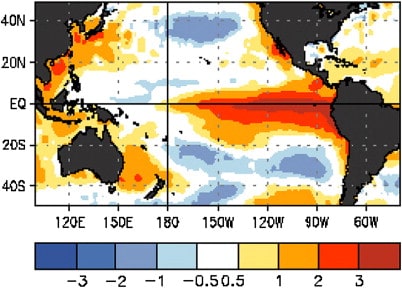

Tropical storms tend to be most severe during an El Niño event, mainly because the sea water temperatures are much warmer than normal and this provides the energy needed to fuel a storm. Unseasonably high water temperatures, one of the more severe coral threats, can be especially harmful to the corals, causing the corals to bleach and die. Perhaps the most severe coral bleaching event on record in this region occurred during 1998, and this was followed by another bleaching event in 2002. While mild bleaching has occurred in some locations over the last decade, there has not been a mass coral bleaching event here in over a decade.

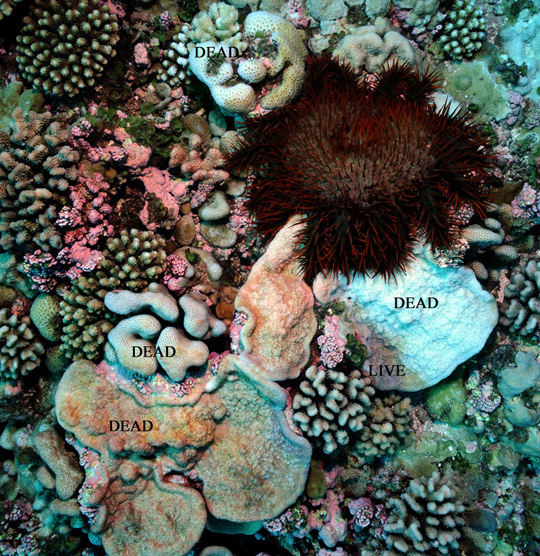

One of the more publicized coral threats, crown of thorns starfish (COTS) have received a lot of attention since outbreaks were first reported in the early 1960s. These starfish can reach 40 cm in diameter; they have 8-21 arms, and a body covered in poisonous spines. Crown of thorns starfish, or COTS, feed by inverting their stomach onto the coral and excreting enzymes, efficiently digesting the living tissue and leaving behind a stark white skeleton. During COTS outbreaks, thousands of animals can invade a reef, devastating every coral in their path.

In French Polynesia, severe outbreaks of COTS were reported in Society Islands between 2006-2008. During our surveys, we observed low numbers of crown of thorns starfish in Mopelia, Scilly and Bellinghausen. Their impacts were confined largely to deep water (15-30 m). On one dive, we counted several dozen of these animals, extensive amounts of recently killed corals, and large stands of corals that had died a few years earlier; only the skeletons remained.

In Tupai, Huahine and Raiatea, entire reef tracks had been denuded by crown of thorns starfish several years earlier (COTS outbreaks were reported from these areas in 2008). In shallow water, most of the coral skeletons were also gone and replaced by fields of rubble, likely due to Hurricane Oli, while skeletons of the hardier massive corals were still in growth position in deeper water. Even though all of the older corals had been killed, these reefs were carpeted with small corals that were generally less than 1-2 years old.

Why is this important? During the Global Reef Expedition, we are characterizing the condition of the corals, coral threats affecting them, and their response to disturbance. We want to know if the reefs are capable of recovering following catastrophic losses, how fast they recover, and if they are likely to persist in the face of climate change. We have witnessed the devastation of corals from COTS around three areas we have surveyed and we have seen ongoing coral mortality from COTS, but we are also witnessing a progressive, rapid recovery of these communities, demonstrating their high resilience and giving us hope that they will persist into the future despite numerous coral threats.

(Photos/Images by: 1, 5 Amanda Williams, 2 NOAA NHC, 3-4, 6 Dr. Andy Bruckner)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members.

One Comment on “Part 2: Life, Death and Rebirth of a Coral Reef”

zidane

this article is very useful, thank you for making a good article