The Global Reef Expedition: The Largest Coral Reef Survey and Mapping Expedition in History

(2020)

ECO Magazine

ECO Magazine

2020 Special Issue on Coral Reefs

by Liz Thompson

The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation sailed around the world to study coral reefs, returning with maps and data on the status of some of the most remote reefs on Earth

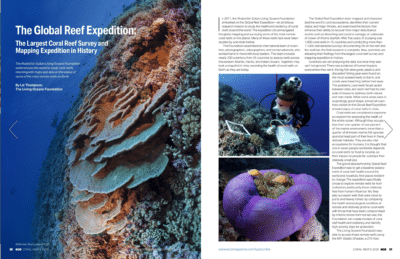

In 2011, the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation embarked on the Global Reef Expedition—an ambitious research mission to study the health and resiliency of coral reefs around the world. The expedition circumnavigated the globe mapping and surveying some of the most remote coral reefs on the planet. Many of these reefs had never been studied by scientists before.

The Foundation assembled an international team of scien- tists, photographers, videographers, and conservationists, who worked hand-in-hand with local leaders. This team includes nearly 200 scientists from 25 countries to assess reefs across the western Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Together, they took a snapshot in time, recording the health of coral reefs on Earth as they are today.

The Global Reef Expedition team mapped and character- ized the world’s coral ecosystems, identified their current status and major threats, and examined the factors that enhance their ability to recover from major disturbance events such as bleaching and cyclone damage, or outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish. After five years of studying over 1,000 coral reefs in 15 countries and conducting more than 11,000 standardized surveys documenting life on the reef and the seafloor, the field research is complete. Now, scientists are releasing their findings from the largest coral reef survey and mapping expedition in history.

©Keith Ellenbogen /iLCP

Scientists are still analyzing the data, but what they saw can’t be ignored. There was evidence of human impacts everywhere they went: the big fish were gone, plastics and discarded fishing gear were found on the most isolated reefs on Earth, and corals were bleaching before their eyes. The problems coral reefs faced varied between sites, and each reef had its own suite of issues to address, both natural and man-made. While some areas were in surprisingly good shape, almost all coun- tries visited on the Global Reef Expedition showed signs of coral reefs in crisis.

Coral reefs are considered a keystone ecosystem for assessing the health of the entire ocean. Although they occupy less than one-quarter of one percent of the marine environment, more than a quarter of all known marine fish species spend at least part of their lives in these delicate habitats. They are also vital ecosystems for humans. It is thought that one in seven people worldwide depends on coral reefs for food or income, so their impact on people far outstrips their relatively small size.

©Keith Ellenbogen /iLCP

The grand idea behind the Global Reef Expedition was to get a baseline assess- ment of coral reef health around the world and, hopefully, find places resilient to change. The expedition specifically chose to explore remote reefs far from civilization, particularly those relatively free from human influence. Yet, they also surveyed reefs that were close to ports and heavily fished. By comparing the health and ecological condition of remote and relatively pristine coral reefs with those that have been compromised by chronic stress from human use, the Foundation can create models of coral reef health and resiliency and identify high-priority sites for protection.

The Living Oceans Foundation was able to access these remote reefs using the M/Y Golden Shadow, a 219-foot yacht with dedicated laboratory facilities. Also on board was a diving decompression chamber and an onboard aircraft—the Golden Eye—that was used extensively for aerial surveys of coral reefs. This modern and advanced research vessel was made available to the Foundation by Prince Khaled bin Sultan of Saudi Arabia, who donated the use of his own ship for the Global Reef Expedition.

On this epic voyage, the science team observed coral bleaching on pristine reefs in the Indian Ocean and explored the little-known cold-water coral reefs of the Galápagos Islands. They also conducted what was probably the last survey of healthy reefs in the northern reaches of the iconic Great Barrier Reef, before they were decimated by a mass bleaching event.

The first stop on the Global Reef Expedition was in The Bahamas. Here, scientists wanted to see how coral reefs were surviving under the triple threats of climate change, coral disease, and loss of several keystone species.

The Global Reef Expedition then trav- eled to Jamaica, where the Foundation teamed up with local fishers and conser- vation organizations to help establish a fishing sanctuary to preserve local fisher- ies for current and future generations. The expedition continued down through the Caribbean, and across the South Pacific, where scientists came upon many healthy and ancient coral reefs, a giant swarm of sharks, and indigenous communities who protected their reefs with rules set forth by traditional leaders centuries ago.

The scientists mapped and surveyed the reefs down to a one-square-meter scale to better understand their health and resiliency. In the process, they developed a new method to accurately map coral reefs using a combination

of Earth-orbiting satellites and field observations. The first global coral reef atlas was published last year, combining maps collected on the expedition with the Foundation’s previous research in the Red Sea. This database contains over 65,000 square kilometers of reefs and surrounding habitats—by far, the largest collection of high-resolution maps ever made of coral reefs.

The high-resolution maps contain detailed information on the location and depth of different habitats, including the size of seagrass beds and mangrove forests along the coast. All of these coastal habitats are vital components of tropical coastal ecosystems. They help filter water, protect the coast from storms, and provide a nursery habitat for commercial and subsistence fisheries. These maps and information have been shared with participat- ing countries as well as scientific and regulatory organizations, which can be used to develop science-based management strategies to protect and restore coral reef ecosystems.

In addition to conducting scientific research, the Foundation spent time with local communities to explain the study, share preliminary results, and discover how community members use the reef and what changes they have witnessed over their life- times. The Global Reef Expedition also brought along educators to teach local students about coral reef habitats, and award-winning filmmakers and photographers to capture the journey, documenting what the scientists saw underwater.

Now that the field research is com- plete, Living Ocean Foundation scientists are analyzing the data and publishing scientific reports about the status of coral reefs in each country visited on the Global Reef Expedition. The Foundation recently released reports on the state of coral reefs in French Polynesia, Tonga, the Cook Islands, and New Caledonia. It will soon publish reports from their research mis- sions to the Solomon Islands and Palau.

So far, this research has informed the creation of a marine protected area (MPA) in Pedro Bank, Jamaica, and in Lau Province, Fiji, and is currently being used to inform marine spatial planning efforts across the South Pacific.

As more data becomes available, the Foundation will share the information with local resource managers and relevant government officials to protect and conserve reefs most likely to survive the coral reef crisis.

Using the data collected on the expedi- tion, the Foundation hopes to identify

the critical ecosystem components that promote coral reef resilience and produce practical reef management tools. The scientists are now working across vast geographic scales to see what factors are most important to maintaining the structural integrity and health of reefs. By improving our understanding of these essential ocean ecosystems, we can better make predictions regarding the future health of coral reefs, including their capacity to adjust to climate change. The Foundation will also develop science- based tools and decision aids that can support plans to mitigate threats to these life-supporting marine ecosystems. Models are being created with the maps and data collected during the expedition that will allow us to make comparative assessments of coral reef biodiversity, oceanographic conditions, and human pressures. These models will describe the status of coral reef health, identify major threats, and determine processes and factors that control marine ecosystems’ health and resilience worldwide.