Clear, scientific information helps policy makers to make decisions about marine management, but it’s rare that they keep everyone happy. But what about when the information is clouded with differing opinions, how do you make decisions that balance conservation and sustainable use then? A look at what has happened to pink and red coral sheds light on just how complicated things can get.

Red Coral: A Valuable Asset

Red coral is a stunning blood-red color. For hundreds of years master jewelers have transformed the coral skeletons into strings of beads to adorn the necks of the wealthy. Since as far back as the 5th century BC people have been using pink and red corals to ward off danger, protect from the evil eye, decorate their battle spears, bring financial prosperity and cure infertility. With such varied and mystical powers at their command it’s no wonder that these corals have been in high demand.

Red Coral in the Mediterranean

In the 1800’s coral fishermen in the Mediterranean used small rowboats and wooden dredges to tangle the coral and haul it up by hand. Leap forward to the 1970’s and motor boats are pulling hydraulic metal dredges that go deeper while SCUBA divers collect the coral from the crevices and cracks that the dredges plough right over.

The static slow-growing coral could not possibly keep up with this intensified fishing and not surprisingly coral harvests plummeted. By the mid 1980’s the United Nations had taken note of the downturn in in the coral fishery and put some rules in place (notably a ban on dredge fishing) to protect the coral. However, the fishery continued to cause concern and by 2007 the US and the EU proposed that red coral be protected using trade restrictions through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES as it is known.

Protecting Red Coral

Proposals to protect the red coral by listing it on CITES were shot down. Industry lobbyists stated they’d rather manage the coral themselves than have a large international body do it for them. Since then local managers have been in charge and red coral harvests in the Mediterranean have been on a steady increase, proof that local management strategies are working and that there is plenty of red coral thriving underwater. Right?

Red and Pink Coral in the Pacific

Across the world in remote parts of the Pacific Japanese and Taiwanese fishermen had been working offshore, collecting pink and red coral from the seabed for over a hundred years. In the 80’s their coral harvests began to go down dramatically and eventually the fishery ceased. Investigations into why the coral harvest declined revealed that in the late 70’s the Japanese government terminated fishing incentives causing many of the coral fishermen to leave. Then the government capped the number of fishing boats allowed in the coral fishery and more fishermen left. The previously intense fishing had created a glut in the market, often of poor quality coral, this caused the price of coral to drop and it was no longer profitable to be an offshore coral fisherman and the last few coral fishermen left.

So you could be forgiven for thinking that pink and red coral are healthy and sustainably fished because the Pacific downturn in coral harvest was caused by reduced fishing pressure, and in the Mediterranean local management is working. It’s a nice story and certainly one that the red coral industry has latched onto. But unfortunately it seems unlikely to be true and could be standing in the way of real protection for red coral.

The Other Side of the Story

A closer look at the coral fishery in the Pacific reveals that by the time the coral harvest was going down much of the coral being brought to the surface was already dead, hence the poor quality, fragments broken off by dredging done much earlier. And, fishermen were not really fishing where they said they were. Coral poachers had spread as far as Hawaii in search of new coral. In 2008, more than twenty years after the fishery had stopped harvesting coral, an underwater survey failed to find a single large patch of live red coral in the fished areas. In fact, instead of being a sustainable fishery it was more akin to strip mining or clear cutting of forests. Across the Pacific each time a new source of coral was discovered multiple boats came to harvest huge amounts of coral until the coral was virtually wiped out and the harvest no longer profitable.

The Pacific and Mediterranean fisheries are conducted differently but now we know how misleading the data from the Pacific was can we really take the Mediterranean coral landing data at face value when such a valuable commodity is at stake?

Under the Surface in the Mediterranean

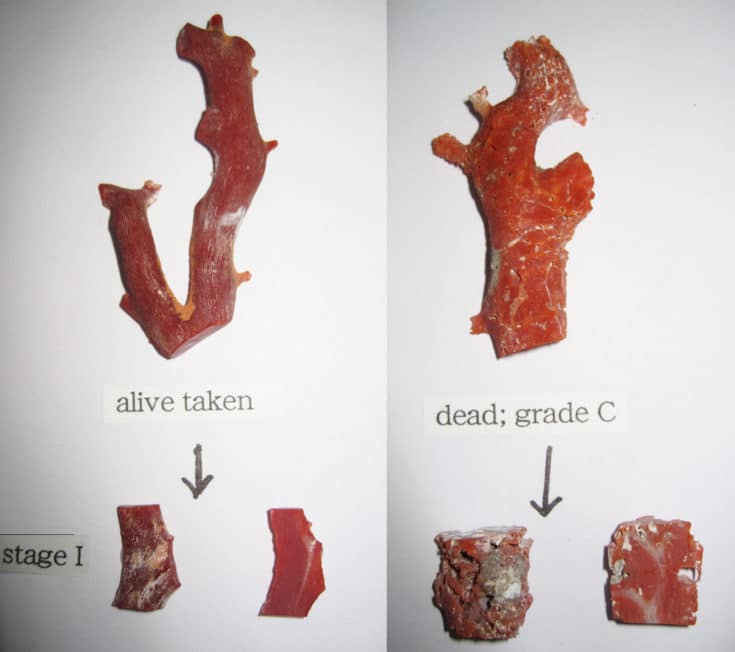

The amount of coral brought to the surface in the Mediterranean is measured by weight and the weight of coral harvested has remained the same, or even increased over the last few decades. But there are three reasons why this is deceiving.

First, studies show that the size of harvested coral is going down. Fishermen have already removed all the large corals and are now collecting the smaller ones. In Spain, France and Sardinia scientists have documented a dramatic 80-90% decrease in the size structure of corals living within scuba diving depth.

Secondly, new diving technology like Nitrox or rebreather systems mean divers can go much deeper. In Italy the red coral harvest more than doubled between 2005 and 2009 as divers reached previously untouchable coral living below 100 meters.

And thirdly, coral fishermen are harvesting coral from new places. The total coral harvested across the Mediterranean in 2007 was almost identical to the total in 1987, both approximately 40 million tons. However, coral from Tunisia accounted for roughly 2.5 million tons in 1897 but amounted to about 10 million tons in 2007, that’s a quarter of all coral taken that year.

Red Coral: Is There a Future

It adds up to a worrying picture. A few small corals spread across the Mediterranean cannot reproduce fast enough to repopulate shallow areas that have been previously fished. The larger the coral, the more it can reproduce. Without any large corals left on the reef recovery of previously fished areas is unlikely. And, limits on the fishery by using total harvest quotas and gear restrictions are failing the coral. The fear is that without significant changes to existing regulations the coral will not be able to sustain current fishing pressure for much longer.

A detailed paper on this topic “Advances in management of precious corals in the family Corallidae: are new measures adequate?” By AW Bruckner, is in this April’s edition of ‘Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability’.