Like other animals, corals need to reproduce to survive. Unlike most other animals, corals are attached to the seafloor and cannot move around to find a mate for coral reproduction. To address this challenge, corals have developed several alternative reproductive patterns and modes of development. Some corals have separate sexes (gonochoric), while others are both male and female at the same time (hermaphroditic). Since self-fertilization is rare in coral reproduction, every coral still needs a partner if they are going to successfully reproduce.

Coral Reproduction Strategies

Usually, coral reproduction is accomplished through synchronous, or mass spawning, whereby all colonies of a particular species release millions of gametes in unison, once per year, for a few hours, a certain number of days after the full moon (the exact timing is well documented and predictable from year to year). The eggs and sperm typically float to the surface, where they encounter other gametes of the same species, and fertilization occurs. The larvae then drift with the current for days to weeks, until they find a suitable place to attach and transform into a polyp. Very few of these larvae survive.

Other colonies are known as “brooders.” They may reproduce more frequently (sometimes monthly), usually producing fewer gametes at a time. Brooders need to be in close proximity because the female colony must take up sperm from the water column, and fertilization occurs internally. When the larvae are released from the female, they are better developed and have higher survival rates. They settle onto the reef and transform into a polyp much sooner.

Although sexual reproduction is the most common and the most important type of coral reproduction, corals also reproduce asexually by cloning themselves. A coral grows by constantly adding new polyps through a process known as budding. Corals can also increase in abundance through fragmentation, where branches that break off during storms reattach and continue growing. Other unique asexual reproductive strategies exist including polyp bailout, polyp expulsion, and asexual production of larvae; these offspring all lack a skeleton when first produced.

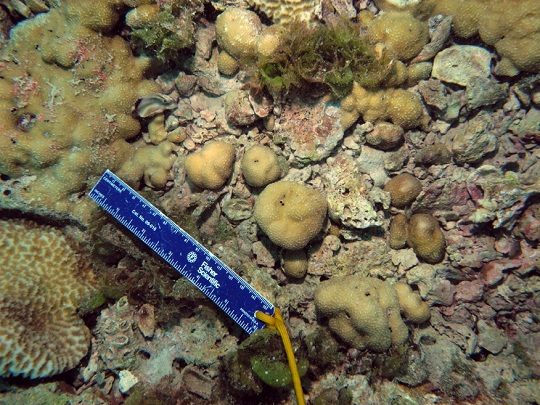

A more unusual coral reproduction strategy involves the production of “gemmae.” A single gemma starts as a mass of soft tissue on the sides or top of the coral that eventually develops a skeleton. It continues to grow, forming a small knob that will detach from the parent. The detached gemma looks just like the parent, except they are round or oval and completely covered in live tissue.

In the lagoonal habitats of Hao, one of the dominant frame-builders is the pore coral (Porites). This coral is long-lived, forming mountainous-shaped colonies that are several meters tall. During our surveys, we found very few small colonies produced through sexual coral reproduction. This raises the question of how these corals are able to spread so successfully throughout the lagoon. Because wave action is minimal in lagoonal habitats and these corals produce a rigid skeleton, fragmentation is unlikely to be an important reproductive strategy. Until yesterday, we rarely found small fragments, as well.

On our fifth lagoonal dive, I encountered a very large (4 m tall) and very bumpy colony. Littered over the substrate and in depressions on the colony surface were hundreds of round to oval gemmae that ranged in size from 1 to 5 inches that originated from the colony. Most had tissue covering their entire skeleton and appeared to be actively growing, but they were completely unattached. The high number of these “rolling stones” produced by one colony of Porites, and their high survivorship, suggests this may be an important mode of coral reproduction for Porites in the Hao Lagoon.

(Photos by: 1 Eddie Gonzalez, 2-5 Dr. Andrew Bruckner)