Reef Resilience

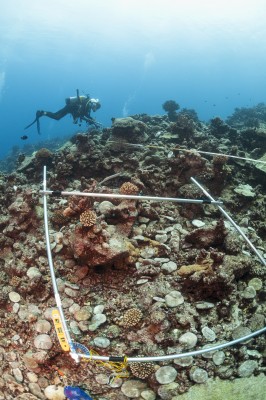

During our research at sea we take measurements and collect data to help us determine a reef’s resilience

What is Reef Resilience?

In a nutshell resilience is the ability of an ecosystem, like a coral reef, to both resist change and recover from it. There are two components:

- ecological resilience – which refers to the amount of disturbance a system can withstand without changing to an alternate stable state, e.g. changing from a coral dominated reef to an algal reef.

- engineering resilience which refers to the reef’s ability to resist changes and the time required to return to their original equilibrium after the system is disturbed.

How Do We Measure Reef Resilience?

To measure resilience we seek to understand the properties of a healthy, stable, coral reef without disturbances. This would be a coral reef with:

- high coral cover and low levels of fleshy seaweed

- a balanced community of fish and motile invertebrates on every level of the food web. Healthy populations of detritivores these are creatures like sea cucumbers that eat decomposing fragments of plants and animals, herbivores or plant eating creatures like sea urchins, parrotfish and surgeonfish, invertebrate feeding fish and fish-eating fish like sharks and barracudas.

- low input of human pollutants like nutrient and sediment runoff which result in ocean pollution

- few nuisance species (like crown of thorns starfish)

- upstream sources of larvae to replenish populations

What is a Disturbance?

If this system is damaged by a short term disturbance such as a hurricane, coral bleaching, an outbreak of disease or coral predators such as crown of thorns starfish, it could recover. If the reef is healthy with wide species diversity it will be better able to resist these kinds of events and recover from them. However, depending on the magnitude and frequency of these disturbance as well as the resistance of the reef the system could reach a tipping point and most or all of the coral may disappear.

Reef Resilience

Ecological feedback loops can determine how the reef will fare in the future. Too many short term disturbances that kill coral can allow algae to settle, reduce the coral’s ability to reproduce, and diminish the reef and number of fish it can support. This downward spiral can lead to the reef changing from mostly coral to mostly algae.

Ecological feedback loops can determine how the reef will fare in the future. Too many short term disturbances that kill coral can allow algae to settle, reduce the coral’s ability to reproduce, and diminish the reef and number of fish it can support. This downward spiral can lead to the reef changing from mostly coral to mostly algae.

Alternatively, safeguarding healthy populations of reef species can maintain high reef resilience. For instance, algae eating fish and invertebrates can prevent a shift to algal dominance. This creates space for new coral to grow which in turn helps restore the structural complexity of the reef, providing habitat for other interdependent species.

Related Publications:

-

2022

Ocean Decade unveils new set of endorsed Actions on all continents

By IOC-UNESCO World Oceans Day: June 8, 2022 UNESCO has announced the endorsement of 63 new endorsed Actions in the context of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021-2030 (the ‘Ocean Decade’). The announcement adds to …

-

2021

Global Reef Expedition Final Report

The Global Reef Expedition Final Report summarizes the findings from our 10-year research mission to survey and map coral reefs across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans as well as the Red Sea. The Expedition involved hundreds of research scientists …

-

2017

Coral Bleaching and Mortality in the Chagos Archipelago

Coral Bleaching and Mortality in the Chagos Archipelago Atoll Research Bulletin, November 2, 2017 By Charles Sheppard, Anne Sheppard, Andrew Mogg, Dan Bayley, Alexandra C. Dempsey, Ronan Roche, John Turner, Sam Purkis Abstract The atolls and coral banks of the Chagos …

-

2016

El Niño’s warmth devastates reefs worldwide

This article on how El Niño’s warmth devastates reefs worldwide, published in Science magazine, references Living Oceans Foundation Coral Reef Ecologist Alex Dempsey and focuses on the impact to the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) which the Foundation surveyed as part of …