Reef building corals start out from a small larvae (planula) that settles onto the reef, or from a fragment that has broken off another colony. The polyps that make up the coral divide, repeatedly, into two or more daughter polyps, growing slowly upwards and outwards and depositing limestone as they grow. They can, theoretically, continue to increase in size for decades or even centuries, eventually forming immense colonies that may be many meters in diameter, especially if conditions are very stable. If the environment changes or there is a catastrophic disturbance such as a cyclone, coral bleaching event, or disease outbreak these corals may die, or lose part of their tissue.

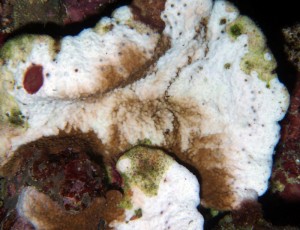

In the past, reefs of Lau Province have been impacted by these and other stressors, but they have shown remarkably high resilience, rebounding quickly. Our surveys have allowed us to identify areas that have been impacted and document patterns of recovery, and we’ve also identified various threats affecting the corals now. We’ve seen very little disease and only minor cases of bleaching, but we do frequently see corals with recent tissue loss – areas on the colony that have no tissue and are stark white.

Sea Snails Easily Mistaken for Coral Disease

It is easy to mistakenly identify these lesions as disease – they typically manifest at the edge of the coral and spread across the colony in a linear fashion much like white band disease. However, upon careful examination, the culprit can usually be found. Perhaps the most egregious and common cause of tissue loss we’ve seen is caused by coral predators, better known as corallivores. Among the corallivores seen here, the most common is the marine gastropod in the genus Drupella. This sea snail typically aggregates on the margins of coral, feeding by night and retreating into the branches or under the coral during daylight.

Drupella gastropods are unusually abundant on these reefs. While it is hard to pinpoint the cause of their high numbers, it is possibly due to an absence of predators. We’ve seen very few of the fish that feed on these sea snails, which may be a direct result of overfishing.

Fortunately, the sea snails are primarily targeting the fastest growing and most common corals found on Lau’s reefs, such as staghorn and table corals (Acropora) and cauliflower coral (Pocillopora). For now at least, settlement and growth of new corals of these species is exceeding the numbers of corals the sea snails eat.

Photos/Images by: Andrew Bruckner

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook!