Expedition Log: BIOT – Day 20

For some divers, sponges are just unspectacular filter feeders hidden among corals, algae and other organisms but for others, including me, they are fascinating organisms. On many tropical Pacific reefs they are relatively uncommon, and consist mostly of small encrusting and cryptic species. This was not the case during our reef surveys in the Chagos Archipelago, however. On every dive, we encountered many different shapes, colors and taxa of sponges, some small and rope-like while others formed large barrels and tubes.

Sponges are simple structured organisms in the phylum Porifera lacking any real organs or tissues. They consist of multiple cells which fulfill different tasks. For instance, the so called flagellated Choanocytes create the interior water flow and trap particles while the mobile Archaeocytes play a crucial role in digestion and cleaning – the latter have the potential to modify themselves into all different cell types existing in the sponge body. It is fascinating that even without any brain or nerve cells they were able to survive millions of years and they become more and more abundant on the sea floors around the world – They are in fact the oldest living animals on the planet.

The simplicity of the body plan structure of sponges is in stark contrast to the overwhelming diversity of their colors and shapes. While conducting transects, the variety of sponges amazes me every time anew. Depending on their environment they can form huge barrels up to 2m in diameter, ropes, balls, vases, tubes or just grow encrusting. Based on their skeleton which consists of mineral spicules and in some species of the collagen protein spongin, sponges can be categorized into four different classes with Demospongiae representing the largest group. It is estimated that there are over 15,000 species of which only about 7,000 have been scientifically described. Identification of sponges is quite tricky and requires a close investigation of the skeleton.

Some examples of the variety of sponge shapes.

Upper left: Acarnus topsenti, upper right: Neopetrosia sp.

Lower left: Dragmacidon reticulatum, lower right: Carteriospongia foliascens

The sponge Leucetta chagosensis—an endemic species in the Chagos Archipelago.

Besides their appealing appearance, sponges provide essential services for the coral reef environment. They are capable of filtering a vast volume of water — they are pumping a volume of water adequate to their own body volume every five seconds. Sponges have an insatiable appetite leaving behind plankton-depleted layers over the benthos of coral reefs. Besides plankton, the complex system of channels and chambers traps bacteria and other fine particles as well enhancing water quality. In plankton poor environments, like in the deep sea, some species can adapt their feeding strategy and prey on small copepods. Following each catch, migrating cells engulf the prey completely within 12- 24 hours. As a consequence, the shape of the carnivore sponge changes as well.

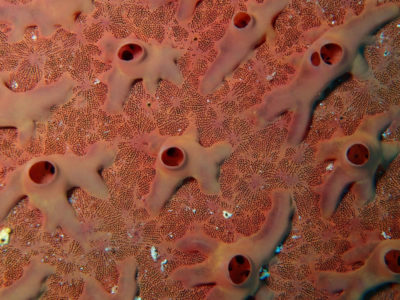

A closer look at the structure of sponges – the surface is perforated by multiple pores: the ostia (smaller pores), through which the water enters the body and the oscula (larger pores), through which the filtered water is released into the environment.

Upper left: Spirastrella sp., Upper right: unknown

Lower left: Placospongia sp., lower right: Most likely Pseudoceratina or Suberea

Besides their positive properties some sponges can present a threat to scleractinian corals. In competition for space they produce acid metabolites which enable the sponge to bore into corals by dissolving their calcium carbonate skeleton. In stressed reefs where corals are weakened by pollution or elevated sea water temperatures, the growth of sponges is favored.

In the southern area of Chagos, Cliona was the dominant sponge genus. We found large areas (up to 4m²) covered by this bio-eroding sponge (left) being in competition with corals, such as Leptastrea sp. (right).

A Porites colony pierced by Siphonodictyon mucosum.

On one hand sponges can destroy corals, on the other hand they are valuable for a great number of organisms. They present an essential link between trophic levels and are the reason why the plenty and colorful life of coral reefs can exist in nutrient poor environments. Sponges are efficient nutrient recyclers providing consumable dissolved organic matter to higher levels of the food chain. In addition to this, they can accommodate up to 16,000 other creatures. They host a high number of symbiotic microorganisms like amphipods and on the surface shrimps can be found quite often. When I was diving beneath a boulder protruding out of a reef of the Solomon Islands I found a bunch of these little fellows cleaning a sponge.

A shrimp (Urocaridella sp.) cleans a sponge (Cinachyrella sp.).

Sponges play an important role not only within the coral reef environment as they are of great interest for the pharmaceutical industry as well. They produce secondary metabolites which have been found to be supportive for the treatment of inflammations as well as cancer and malaria.

As simple as they seem to be for some people—sponges are natural wonders.

Photos by Kristen Stolberg.

Support in sponge identification: Nicole de Voogd, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, Netherlands