Expedition Log: Palau – Day 11

On most of the barrier reefs we’ve examined off the south and west coast of Palau, the coral community has been thriving, with 60-90% of the bottom covered in a diverse assemblage of branching, plating and massive corals. Yet this is not always the case. We’ve surveyed four locations so far, one off the oceanic island of Angaur, two off the east side of Bablethuap and one on the northwestern tip of the barrier reef system that have had virtually no coral.

The conditions in these four locations are similar – clear aquamarine waters, no sedimentation and limited nutrients, typical water temperatures, a gentle reef slope and high quality bottom covered in crustose coralline algae– all conditions that are optimal for coral growth.

Why were there so few corals on these sites? If there was a mass bleaching event or crown of thorns outbreak, you’d see the remains – dead skeletons in growth position. But this was not the case, as the reef surface appears to have been scoured clean, and piles of rubble littered the bottom.

Evidence of storm damage: a field of coral rubble.

The Republic of Palau lies just outside of the northern Pacific typhoon belt. Normally tropical storms miss the island. In December 2012, Super Typhoon Bopha approached Palau, but at the last minute it veered to the south. Even though the eye of the storm was over 50 miles to the south, storm waves of 35 feet or more pummeled the eastern barrier reef system. A once vibrant reef was turned into fields of rubble, with storm waves shattering fragile branching acroporids and overturning immense (2 m) massive boulders of Porites.

During Bopha, some of the largest massive Porites colonies were dislodged and overturned.

Less than one year later (November 2013), the eye of Super Typhoon Haiyan passed over Kayangel, a small atoll a few miles north of the main island and barrier reef system. While few surveys of these northern reefs have been undertaken, our initial glimpse reveals similar catastrophic damage. All of the branching corals are gone and only a few smaller hardy massive corals remain.

In some respects, a coral reef is like a forest. There needs to be the appropriate substrate for initial settlement and colonization (soil for plants, rock for corals). The first things to settle in the forest are weeds, grasses and other small plants – in the case of the reef, ‘weeds’ are the small, short-lived coral species, many of which brood their eggs and release well developed larvae ready to settle almost immediately. On Pacific reefs, the first corals to settle are early colonizers such as Pocillopora and Acropora.

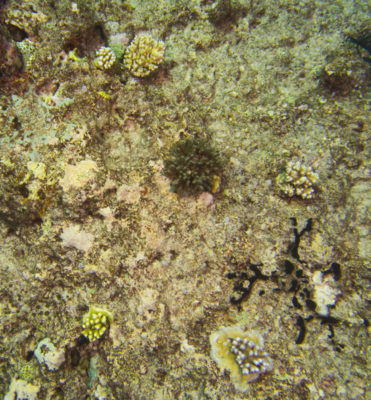

The reef has begun to regenerate from the typhoon damage. A few weedy species of corals have settled and are slowly growing.

In addition to the reef substrate, dead corals, such as this dead table acroporid, provide an ideal substrate that can be colonized by new corals. In this example, there are over a dozen different species of stony corals, a soft coral and an encrusting sponge that have settled and begun to spread across the substrate.

Eventually, bushes are able to colonize, forming a young forest that slowly outcompetes and overtakes the grasses and weeds. On a reef, the ‘bushes’ are the fast growing, branching corals such as Acropora and Seriatopora, as well as some of the smaller plating and potato chip-shaped corals such as Pavona cactus.

Two years after the storm, several species of corals such as Pocillopora, Stylophora and Acropora have reached sizes of 3-5 cm and a fewe smaller massive corals are present.

Over time in the forest, larger deciduous trees like the oak and maple tree will appear. Similarly, sturdier massive corals such as the faviids as well as many of the plating and foliaceous corals such as Montipora, Merulina, and Leptoseris begin to colonize the reef. This is also when you have the highest diversity of corals (or plants).

On reefs that have not been disturbed for many years, a high diversity community can become established.

Finally, the climax community becomes established, outcompeting many other species. In a forest, this may be the majestic redwood trees, pine trees or other evergreens. These are the largest and longest living species. On a reef, this would be the longer-lived massive corals, especially the important frame building corals like Porites. These species take the longest to become established and they eventually grow to several meters in size, but this takes hundreds of years. Fortunately, many of these longer lived corals tend to be more resistant to strong waves, and often they resist the most severe of storms… but not always, as evidenced by the two super typhoons that struck Palau in 2012 and 2013.

Over time, some of the larger, long lived species such as Pocillopora and the larger table acroporids can dominate in shallow water.

The good news is that Palau’s reefs seem to be very resilient. Already, we are seeing many small recruits – baby corals – that have settled on the open substrate and are beginning to regrow.

Photos by Andy Bruckner