Our morning dive at Sandy Point was like travelling through time, with glimpses of the past and a foreshadowing of future directions of Caribbean reefs growth visible simultaneously. Built on a foundation of 200-500 year old corals, many over 5 m in diameter and 7-8 meters tall, the reef consisted predominantly of star coral colonies (Montastraea faveolata) that were completely live back in 1990. These corals grew together like a chain of mountains, extending from depths of 25m to 10-12 m below the water’s surface.

The shape of many of these Caribbean reefs corals was similar to a child’s drawing of a Christmas tree – each colony having a sharply pointed peak, with a series of overlapping shingles layered down the sides. Other corals were reminiscent of the moguls on an expert ski slope in Colorado, although they were colored golden brown, green and dark brown instead of white.

Well, this is what Caribbean reefs looked like for hundreds of years, until they began to succumb to diseases and bleaching. During the first of the mass bleaching events in the 1980s, the corals turned white, but they regained their symbiotic algae, their color and health. This began to change after the 1995 bleaching event. New diseases emerged, including yellow band disease and white plague. Yellow band caused a slow death, with colonies showing progressive loss of tissue (a cm or so per month) over a period of 10-12 years, while white plague spread through populations like a wildfire, denuding tissue at rates that exceeded 1-2 cm per day. Due to the combined effects of these forces, and subsequent bleaching events, living tissue disappeared quite rapidly, and colonies were progressively subdivided into smaller tissue remnants.

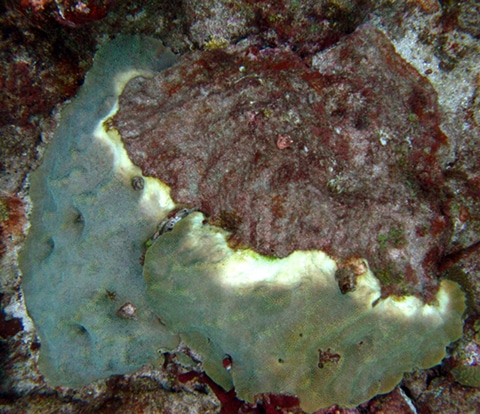

Fortunately, many of these corals are still partially live. The original skeletal structure is visible in areas that died, and sheets of living tissue cover other areas of the colonies. Mortality was patchy and randomly scattered throughout the reef, as we found small areas of vibrant star coral colonies adjacent to corals that were completely dead. In some cases the live parts of the coral (tissue remnants) were continuing to shrink in size from disease, coral predators, and competition and overgrowth by fleshy algae, tunicates, sponges, and other nuisance species. In others, these tissue remnants were beginning to regrow.

Will these remaining patches of live tissue slowly resheet over their original skeletons? It is possible, if the environment is conducive to continued growth. However, it will take a long time, as these corals only grow about 1 cm per year. In other locations, like some of the Caribbean reefs we examined off Cay Sal last month, colonies of star coral were badly damaged by the 1998 bleaching event. Nevertheless, the small surviving parts of these corals have shown considerable upwards growth over the last 10 years. These often resemble the original, larger and older corals, forming a sharply peaked mountainous structure, but they are just much smaller in size.

In the near term, this Caribbean reef is changing rapidly. It still had fairly high living coral cover, but the dominant species are now vastly different. Most of the corals are also much smaller, having settled on the dead star coral skeletons over the last 10-15 years, and slowly increasing in size. Most of these were mustard hill corals (Porites astreoides), a “weedy” species of coral that has high rates of settlement and survival (recruitment), but tends to have a shorter lifespan than massive corals like star coral. There were many other species of corals, as well, including species we had not yet seen on our dives in St. Kitts. We saw flourishing thickets of branching cactus coral (Madracis mirabilis), large plates of scroll coral (Agaricia lamarcki), brain corals (Colpophyllia natans and Diploria spp.), and other corals.

This reef was unusual in other ways as well. I’ll talk a bit about some of our other observations in the next post.

(Images/Photos: Andy Bruckner)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and our team members.