“The area was swarming with large sharks—or ‘gobblers,’ as we called them…The gobblers were a constant problem. At times there were as many as twenty nearby. They were of all species and sizes.”

That’s what underwater archaeologist and treasure hunter Robert Marx said of the waters surrounding Serranilla Bank after an expedition here in 1964. Marx was looking for the remains of the 15 gold-laden Spanish galleons that sunk here during a hurricane in 1665.

It’s hard to say how much Marx might have been stretching the truth. The book he wrote about his Serranilla and other adventures came out in 1976. That was one year after the movie Jaws, when people tended to think of every shark as a man-eating menace.

Marx was almost certainly playing things up a bit to add a little juice to his tales. But there would have been more of Serranilla’s sharks back then. Countless populations have declined severely in the years since he was here. Sharks can be an indicator of healthy reef systems, but so far we’ve seen only docile nurse sharks on our dives.

There may be multiple reasons why we haven’t seen more species. First off, the reefs around here are often patchy without a lot of large reef structure, and the banks slope gently into deeper water. This could mean less shark food and fewer shark species, especially the roving varieties.

Serranilla’s sharks populations in the region could also have been affected by too much fishing. Sharks are especially susceptible to overfishing because they reproduce slowly, making it harder to rebuild a population. And and we’ve heard that there was once shark fishing in this area.

We’ve only seen a handful of fishing boats, none targeting Serranilla’s sharks or any other sharks, and none yet at Serranilla. At least two of those we saw earlier were rigged for collecting conch, which command a good price and are becoming increasingly difficult to find in the Caribbean.

We’ve talked to the men aboard a couple of these boats, one of which came in close a few nights ago. It was a small boat to be this far away from their home, Nicaragua, and so full—a rusty 20-meter trawler with almost 30 men visible on deck and no doubt more below. Our large ship with a string of smaller dive boats behind must have been a strange sight indeed.

They sent a small boat over because the air compressor that they use to supply divers was broken and they wondered if we might have a belt they could use to fix it. But as well equipped as we are, we had no belt to offer. They didn’t seem to give any thought to the fact that they were using their air compressor and their boat illegally in these waters. Fishing requires Colombian permission, and the country doesn’t allow conch harvest for export.

We have a representative from the Colombian navy on board. He tells us it would take at least 3 days for a Colombian patrol boat to reach fishermen on these banks, and by then who knows where they would be. For now, I guess, the key to protection for the San Andres Archipelago’s remote reaches is location, location, location. Some fishermen will come, but very few can.

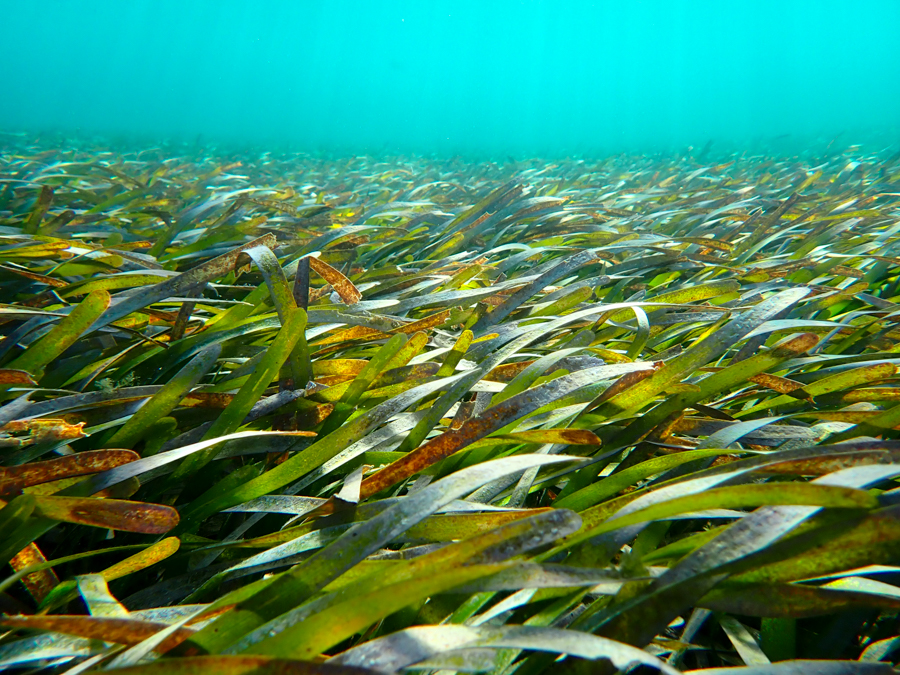

Serranilla’s sharks certainly haven’t been a problem as we’ve made our way around the area searching for good reefs. The still moderately rough seas, on the other hand, have made the dives a little challenging. So far we’ve found only shallower reefs where the seas push everybody back and forth as they try to do their research. It takes a little more work on such dives, but we’ve been rewarded with views of some interesting coral encrusted gulches filled with plenty of fish, and an oddity here and there like a slipper lobster or a toadfish.

At this point we’d actually love to spot something besides a nurse shark, but lets just say we’re not expecting to ever enter the water and have to fight off four makos and two lemon sharks, as Marx claims to have done on one dive. That’s probably about as likely as us happening upon one of those 17the century wrecks. All the same, though, we might just look a little more closely at the rubble piles around the reefs on our way back to the boat.

(Photos/Images by: 1,3,&5 Mark Schrope, 2 Felipe Cabeza, 4 Brian Beck )

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and team members