The last time I was at Titchfield High School in Port Antonio, Jamaica, I took a moment to look out the window at the old cannons that line the walls separating the school from the clear turquoise waters of the Atlantic Ocean. I was there with my colleagues from Alligator Head Foundation to implement the J.A.M.I.N. program. It’s hard not to let my imagination run wild, wondering what happened on this spot centuries ago when, long before it became a high school, it was a well-armed British defensive structure called Fort George. And so, the story begins…

In the Age of Exploration, between the 15th and 18th centuries, European countries were competing to expand their power and influence around the world, and one of the primary measures of success in this tumultuous race was the conquering and colonization of foreign lands. This colonization would forever change many parts of the world, including Jamaica. Christopher Columbus was the first explorer to set foot on Jamaica in 1494, but his son would later return in 1509 to colonize the country. The original inhabitants, called the “Taino,” were forced into labor and their population quickly declined due to disease and genocide (see Seville – The Birthplace of Modern Jamaica). Subsequently, the Spanish colonists brought African slaves to Jamaica to replenish the shortage of free laborers.

Aside from the obvious moral problems of colonialism, there are other characteristics that make it both a highly unstable and unsustainable practice. History shows that just because a country has colonized another does not mean that it will dominate it forever, or that its reign won’t be contested by another colonizer. Many countries throughout the Caribbean were conquered by multiple European countries, and Jamaica was no exception. Spain ruled over Jamaica until 1655 when the English invaded the country, an event known as the Invasion of Jamaica. The Spanish were beaten in this battle and the island was then acquired by the English Empire.

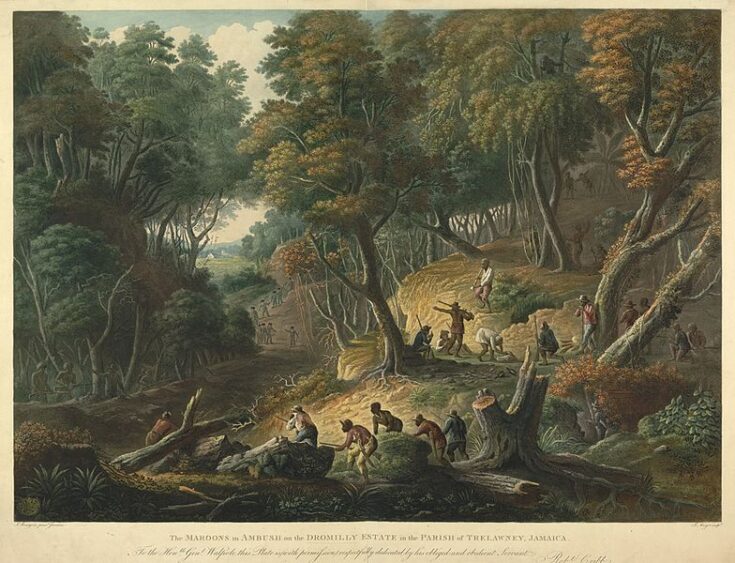

Although victorious, the English found they had to contend with two new enemies on the island: the Spanish guerillas and Jamaican maroons. Not all of the Spanish had fled Jamaica in 1655; some had gone to northern Jamaica to establish settlements. The remaining Spanish engaged in constant guerrilla warfare, which caused large setbacks to English colonization efforts. When the majority of Spaniards had abandoned Jamaica, they also left behind many of their African slaves. These slaves fled to the mountainous interior to form three different settlements. The English referred to them as maroons. Understandably, the idea of being captured and acquired as property by another European power was unappealing to the maroons, and so they engaged in numerous armed conflicts with the English.

In an effort to completely drive the Spanish from Jamaica, English Governor Edward D’Oyley negotiated with the leader of one faction of the maroons, Juan de Bolos. As part of the resulting agreement, the maroons were offered the same terms as British settlers, so long as they helped to rid the country of the Spanish. Over the next couple of years, the maroons helped to conduct raids against the Spanish and any other factions who remained hostile towards the English. Eventually, the Spanish were completely driven from Jamaica in 1660. Shortly thereafter, the English appointed Juan de Bolas the Colonel of the Black Militia.

Not all maroons aligned with the English, however. One maroon faction, lead by Juan de Serras, opposed the English and continued warfare against them. During an ambush in 1664, they killed Juan de Bolas, which initiated the unraveling of the relationship between the Juan de Bolas maroons and the English. The maroons and the English continued to wage war against each other until slavery was abolished in 1838.

In the mid-17th century, plantation owners in Jamaica switched from growing cotton and tobacco to growing sugar cane. Jamaica became the largest exporter of sugar in the British Empire, and hundreds of thousands of slaves were brought to Jamaica to farm the crops. To protect this valuable asset from invading ships, a number of forts were erected along the coastline. One of them was called Fort George.

The fort was constructed in 1729 and named after Great Britain’s King George I. An imposing stone complex, it was constructed with walls ten feet thick and lined with 8 cannons and 22 guns. It was erected specifically to provide protection from both foreign invaders as well as the Jamaican maroons, who by this time were living nearby and still attacking frequently enough to be deemed a serious threat by the British.

Now, hundreds of years later, Titchfield High School occupies the place where the Fort George’s barracks once stood. The school originated in Port Antonio in 1786 in an area called the “Free School,” but transferred locations to Fort George in 1886 after the Jamaican School Commission leased the barracks from the government. Today, only remnants of the fortress still stand. These remaining structures are protected by the Jamaica National Heritage Trust.

Every time I look out the classroom windows of the school, the cannons and stone walls are a reminder of Jamaica’s turbulent past. For me, the school symbolizes progress. In the not so distant past, Jamaicans have overcome incredibly difficult hardships with perseverance and determination, and this has led to the development and growth of an independent nation with a vibrant culture and a thriving education system.