Afternoon Dive

A major component of our work during the Global Reef Expedition focuses on understanding factors and processes that enhance the resilience of coral reefs (reef resilience). We evaluate a number of ecological, physical and chemical parameters at each reef we visit, which allows us to compare and rank reefs within a single location and across large spatial scales to come up with a coral reef health index. We combine data on coral population structure, recruitment, health and disease, algal community assemblages, degree of herbivory, fish community structure and biomass, and other parameters we collect during our rapid assessments to determine reef resilience We will then develop recommendations on actions that can be taken to either protect that resilience or enhance it in stressed locations.

This approach is being taken by other researchers as well, but the parameters that are measured vary and the strategy to compare the reef resilience also varies. What is your baseline for a healthy or resilient reef? Is the best location in a particular country or region the highest ranked site and all others are ranked against this standard? Is a reef that is considered in near-pristine state (which is difficult to find nowadays) the standard and all others are compared against this standard? Is a reef that has changed significantly due to a widespread decline of one of the most important reef building corals (star corals), from which recovery to their former glory would require 100s of years (like many Caribbean reefs) still considered resilient if much of the structure is still present, assemblages of other species are intact, and there are high levels of recruitment, herbivory and other processes we consider essential for a properly functioning reef? What is the reef resilient to?

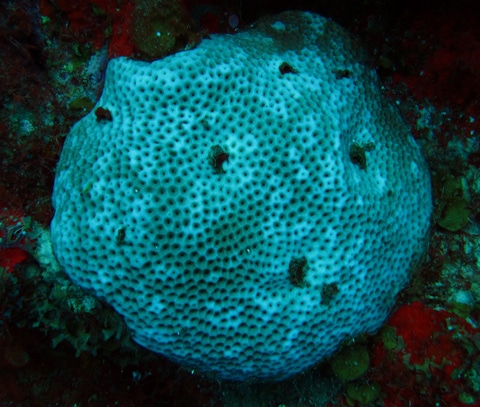

Most reef resilience assessments today are targeting one parameter in particular: coral reef bleaching. Reef-building corals and other organisms have symbiotic relationships with single-celled photosynthetic algae (dinoflagellates), known as zooxanthellae (other similar symbionts occur in sponges and other organisms). These organisms are vital to the health and proper functioning of a coral, providing food, removing metabolic waste products, aiding in calcification and a host of other functions. Bleaching is a phenomenon where the coral animal (polyp) becomes stressed and the zooxanthellae are expelled, or the zooxanthellae lose their photosynthetic pigments, and the coral becomes pale, or in extreme cases stark white, as if someone poured chlorine bleach on the coral.

Corals have been known to bleach since at least the early 1900s, but it is only since 1982 that regional and global bleaching events have been reported. These large scale events are most typically caused by elevated and sustained higher-than-normal seawater temperatures, often in concert with elevated UV radiation. If a coral bleaches, it can recover, but since 1998 the temperature extremes have been higher than ever before, and they are prolonged. The coral ultimately starves and bakes, eventually sloughing its tissue and dying.

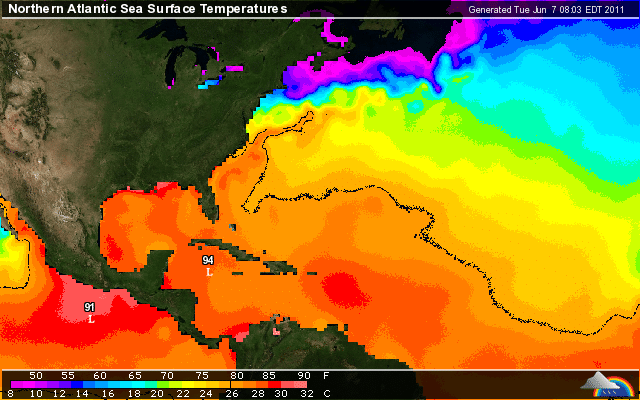

In our coral assessments, we record the degree of bleaching and also evaluate the impacts from past bleaching events. We also take temperature measures of the reef each day and have long-term temperature monitors deployed on many reefs. Usually, bleaching events occur in late summer and early fall, when water temperatures are at their peak. What is worrisome for us is that water temperatures around St. Kitts and Nevis are unusually high for this time of year. We are recording seawater temperatures on the reef of 29.5-30°C (85-86°F). Usually, reef temperatures here are around 28°C (82°F) during early June. It turns out that there is an unusual mass of warm water centered on the eastern Caribbean, directly over St, Kitts. While this could promote the formation of one of the season’s first hurricanes (which would ultimately cool the water once it passes), right now, it is beginning to trigger a bleaching event on these reefs.

The team has been noting an unusually large number of starlet corals, normally dark brown in color, that are pale blue which is a sign of early stages of bleaching.

Our afternoon dive, off Four Seasons Reef in Nevis, appeared to be more severely affected by bleaching than other sites we examined. Not only were the starlet corals bleaching, we recorded bleaching in the large plating scroll corals (Agaricia lamarcki), all of the star coral colonies, lettuce coral, mustard hill coral, and many other species. At this time, none were completely white, but they were pale. Often, only selected parts of the colonies were bleached, while portions that were closer to the reef, under an overhang or otherwise protected from high light levels showed minimal signs of bleaching.

Over the next week, we will continue to follow bleaching on these reefs. We are hopeful that the water will cool and conditions will return to normal, so the corals can undergo full recovery.

(Images/Photos: 1, 3-4 Andy Bruckner, 2 Weather Underground)

To follow along and see more photos, please visit us on Facebook! You can also follow the expedition on our Global Reef Expedition page, where there is more information about our research and our team members.