Fact Friday

The Galapagos is home to many unique species. Galapagos batfish have two sets of modified fins so they can walk along the ocean floor. They also have a retractable appendage on their snout that they can use like a fisherman’s lure.

Photo Credit: Iliana Baums

Background Information

REEF ZONES I

In Unit 10: Reef Types, we learned that there are three main types of reefs: fringing, barrier, and atoll (figure 11-1). Each reef type can be divided into zones. These zones are defined by location and abiotic factors such as depth, wave energy, light intensity, temperature, and water chemistry. It’s important to understand the parameters of each zone because these factors influence the distribution of particular organisms, especially corals. In this unit on reef zonation, we will learn about the characteristics and location of the following reef zones: the reef flat, reef crest, fore reef or reef front, and back reef.

Figure 11-1. a) Fringing reef; b) Barrier reef; c) Atoll

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

While the lagoon is not technically a zone, it can be used to help describe some of the zones. This shallow body of water is separated from the ocean either by a coral reef or by land (figure 11-2). They can contain patch reefs, seagrass beds, coral rubble (broken coral), and sand. Lagoons occur throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans, while smaller ones (not as deep or wide) exist in the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 11-2. a) Barrier reef, Society Islands; b) Maria Est Atoll, Tuamotu Archipelago is an example of a completely closed atoll. The red arrows indicate the location of the lagoons.

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

Water temperature in the lagoon depends on the size and depth of the lagoon as well as the amount of wave action. For instance, a small, shallow lagoon with little wave action may get very hot.

Lagoons that are near mangroves or areas with human development may contain water with high nutrients and low visibility. It is difficult for many species of coral to thrive in this environment.

Fun fact

X

Fun Fact

One of the largest coral reef lagoons in the world is located in New Caledonia, in the South Pacific. It is approximately 9,266 square miles (24,000 square kilometers)! In 2008, the lagoon was listed as a World Heritage Site for its natural beauty, biological diversity, and ecological processes. It is home to many species including threatened sea turtles and marine mammals – it contains one-third of the world’s dugongs.

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

Reef Zones II

Reef Flat

The reef flat is an area that is protected from wave action (figure 11-3). The reef flat can extend for feet to miles (meters to kilometers) and the depth can range from inches to several feet (centimeters to a meter). Corals in this zone have adapted to tolerate a wide range of temperatures, light intensity, and salinity. Additionally, corals have adapted to low levels of dissolved oxygen in seawater. When water temperatures are high (over 104°F/ 40°C), there is less dissolved oxygen in seawater. Sometimes during low tide, corals are exposed to air.

Due to these difficult living conditions, the diversity of life on reef flats is much lower when compared to the other zones. Species in this zone have adapted to these extreme environmental conditions and many are found exclusively in this zone.

Figure 11-3. a) Underwater view of a reef flat; b) The yellow arrow is pointing to the width of the reef flat.

Photo Credits: a) Ken Marks; b) Andrew Bruckner

Reef Crest

The reef crest is the highest point of the reef (figure 11-4). The reef crest breaks waves and receives the fullest impact of wave energy. During low tide, reef crests can be exposed to air. This zone also receives the greatest amount of light intensity, as it is closest to the water’s surface, or even above it. Due to these harsh conditions, not all organisms are able to live here. Corals that do live here must have strong structures that can withstand intense wave action, high light intensity, and aerial exposure in order to thrive in this zone.

Figure 11-4. a) Underwater view of the reef crest; b) The area where the waves are breaking is the reef crest.

Photo Credits: a) Ken Marks; b) Andrew Bruckner

In the Pacific and Indian Oceans, this zone can be dominated by calcareous (composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3)) coralline red algae. In cases such as these, the zone is often referred to as the algal ridge. These hard algae are found in elevated ridges as well as spur and groove reef formations (figure 11-5) that extend seaward. Spurs refer to the areas that form parallel ridges of coral growth, while grooves separate these ridges and contain sediment and coral rubble that has eroded from the spurs.

Figure 11-5. Spur and groove reef formation

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

Reef Front or Fore Reef

The reef front or fore reef (figure 11-6) is found at the furthest distance from shore. It slopes downward and can reach great depths. Sometimes the reef front extends almost straight down forming a vertical wall called a drop-off.

Most corals thrive in the intermediate zone of the reef front between 15-65 feet (5-20 meters) deep. This is where the greatest diversity of corals exist. In both shallower and deeper parts of this zone, diversity declines and some corals have adapted to living at specific depths. Corals in this intermediate zone are exposed to relatively low wave action and light. Often, corals modify their growth forms in order to survive in different zones (see Unit 9: Coral Growth). For instance, plate corals have more surface area allowing for these corals to receive a greater amount of light. This in turn allows zooxanthellae to create food and nutrients for the corals (see Unit 4: Coral Feeding).

Figure 11-6. Reef fronts

© Michele Westmorland/ILCP

Back Reef

The back reef is an area that slopes into a lagoon. The back reef is often shallow and more protected from wave action (figure 11-7). It can be exposed to air during low tide. Isolated patch reefs often exist here as well as coral rubble.

Figure 11-7. The red arrow is pointing to the back reef of the atoll in Tuamotu, French Polynesia. It is the area of turquoise water.

Photo Credit: Andrew Bruckner

Zonation Patterns

Fringing reefs, barrier reefs, and atolls may have different characteristics, yet, they have similar zonation patterns.

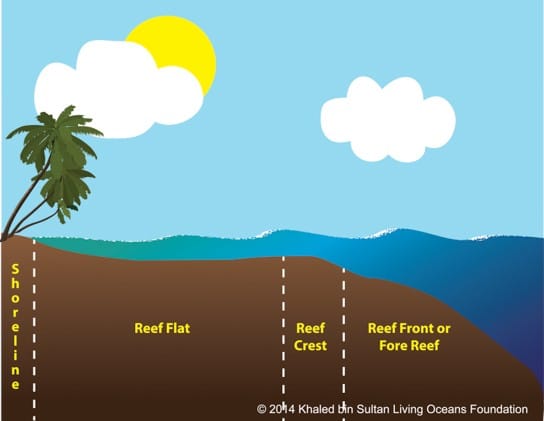

A fringing reef does not have a lagoon or a back reef. The reef flat extends from the shoreline, ending at the reef crest. The reef front is found on the oceanic side of the reef crest. See figure 11-8.

Figure 11-8. Cross-section of fringing reef

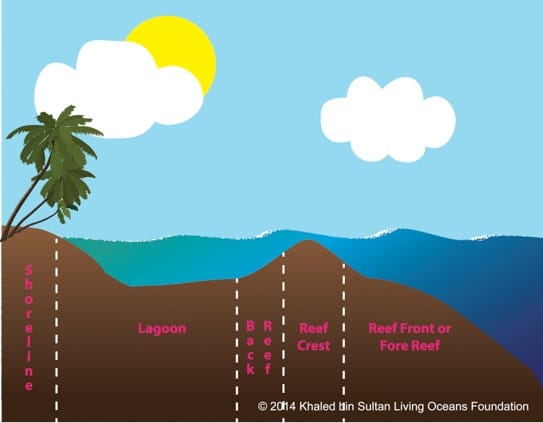

Barrier reefs are separated from land by a lagoon (figure 11-9). The reef crest is bordered by the back reef, on the shore side, and the reef front, on the oceanic side (when there is not reef flat). Barrier reefs can have a reef flat that is found between the back reef and reef crest (not seen in figure 11-9).

Figure 11-9. Cross-section of barrier reef

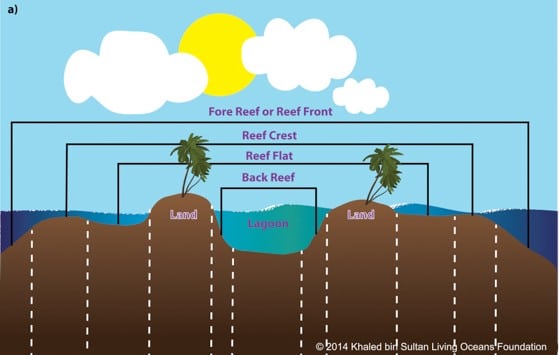

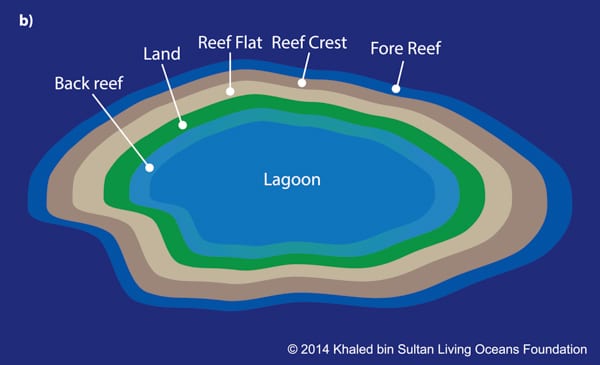

Remember that atolls are a somewhat circular shape. In the center of the atoll is a lagoon, which can be completely enclosed by land (figure 11-2b) or partially surrounded, allowing for water to flow in and out of the lagoon through channels. Most of the reef is on the outside of the atoll. In atolls, reef flats can be found on the ocean-facing side of land (figure 11-10) or next to the back reef (not in figure 11-10). The reef front is found on the outer, oceanic side of the atoll. There can be a back reef on the inner part of the atoll that slopes into a lagoon.

Figure 11-10. a) Cross-section of atoll; b) Aerial view of an atoll

ATTRIBUTION

Figure 11-8-11.10a. Palm tree vector by Sergio Fiallo [CC0 1.0 Universal (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/)], 08 May 2011 via Clker.com. http://www.clker.com/clipart-alone-palm-tree.html.